I read this book in 2019. In light of the recent publish of its Chinese version, I thought I could share some of my reading notes. The ultimate purpose of the book is to emphasize the vital importance of sleep. Through countless examples and theories, the author hopes that the realization of “sleep matters so much” may finally lead people to a more healthy life. I’ve been constantly monitoring my own sleep status ever since and can personally vouch that my overall health and skin quality is in great shape with a simple combination of ample time of sleep and abundant water intake.

Chapter 2: Your Daily Sleep Rhythm

- Sleep is universal in animals, even in insects and worms, despite its apparent drawbacks (vulnerability to predators, loss of time for productivity). When a biological feature is preserved deep in evolutionary history, it is usually a critical function. This must mean sleep is a critical function, and it’s important to understand why it’s important.

How Sleep Rhythm Works

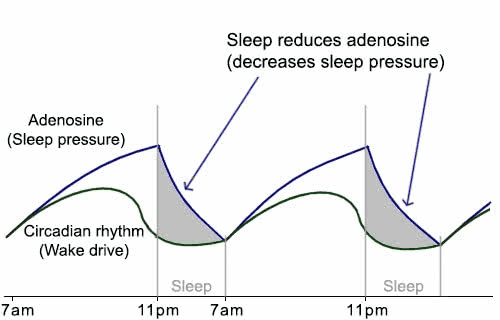

- Sleep is regulated by two mechanisms:

- The circadian rhythm, regulated by melatonin (produced by the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain). Think of this as a natural “wake drive,” making you stay awake during the day and waning during night.

- The circadian rhythm responds to light and darkness to calibrate itself. It’s naturally 24 hours and 15 minutes long on average.

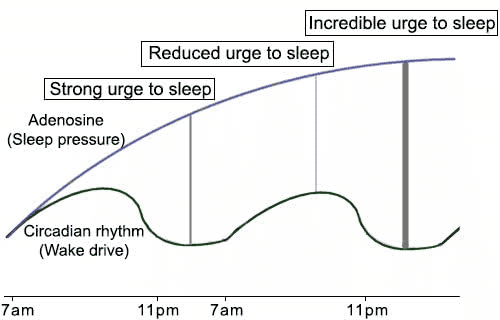

- Adenosine(腺苷) is a fatigue signal and causes “sleep pressure.” This rises consistently through the day without sleep, making you feel more tired. Sleeping depletes adenosine, and you wake up with a lower level.

- The circadian rhythm, regulated by melatonin (produced by the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain). Think of this as a natural “wake drive,” making you stay awake during the day and waning during night.

These two mechanisms interact as shown in this graph:

Notice that sleep naturally happens when the difference between curves is greatest - you feel the greatest sleep pressure from adenosine, and the least “wake drive” from your circadian rhythm.

This explains an odd phenomenon: if you’ve ever had to pull an all-nighter, you might have noticed yourself getting a second wind in the morning, oddly feeling more awake at 8AM than at 3AM. This happens because the circadian rhythm “wake drive” is starting up again, and reduces the adenosine-circadian gap.

Circadian rhythms vary from person to person, depending on when they naturally wake up and have maximum energy. The idea of “morning people” and “night owls” is real.

- Whether you’re a morning or night person strongly depends on your genetics.

- Why would humans evolve with this variation? Evolutionarily, having a mixture of morning people and night owls allows a population to reduce its vulnerability in nighttime to a shorter period of time.

- Example: As morning people sleep earlier (say at 10PM), night owls can keep up the watch. Then as night owls get tired (say around 4AM), the morning people are starting to wake.

- But in modern times, the night owls are heavily punished, since early work times force night owls to sleep and wake up earlier than they would naturally prefer. This reduces performance in the mornings. Furthermore, by the time night owls peak in the afternoon, the workday has already ended.

How You Disrupt Your Sleep Rhythm

- Now that you understand how sleep rhythm works, you can better understand common disruptions to sleep.

- Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, thus reducing how much you feel the “sleep pressure.”

- If you ever drink coffee and then feel a crash later, this comes from caffeine wearing off while adenosine keeps increasing throughout the day.

- Caffeine has a half-life of 5-7 hours, depending on genetics for the cytochrome P450 enzyme in your liver. Some people metabolize caffeine more quickly than others.

- Be careful when drinking decaf, as it apparently contains 15-30% of the caffeine in regular coffee - it’s nowhere near zero caffeine.

- Jetlag disrupts your circadian rhythm

- Jetlag is usually worse when you fly eastbound because adjusting your schedule requires falling asleep when the body wants to be awake. This is more difficult than staying awake when your body wants to sleep.

- Since the circadian rhythm is slightly longer than a day, lengthening it is easier than shortening it.

- How do you know if you have a sleep deficit? Here are a few signs:

- You don’t wake up naturally at the time you set your alarm - this means your body wants more sleep.

- When you read, you often lose track and need to read a sentence twice.

- You feel drowsy just a few hours after waking.

- You need coffee to feel functional.

- Luckily, later in this book, we’ll discuss how to improve your sleeping habits and reduce your sleep deficit.

Chapter 3: Sleep Cycles within a Night

Intro

Now you understand how your sleep rhythm gives a regular schedule of sleep from night to night. Next, we’ll look into how, within a single night of sleep, your brain cycles between different types of phases of sleep. This is important to understanding the function of sleep for your brain.

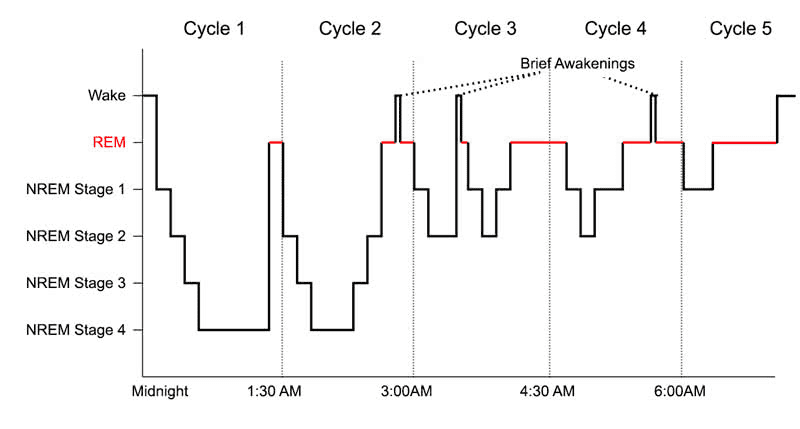

In summary, your brain switches between two types of sleep - REM (rapid eye movement) and non-REM (NREM) sleep. The two types of sleep have different functions - simplistically:

- Non-REM clears out old memories and mental “trash,” and it moves information into long-term storage.

- REM strengthens the valuable connections that remain, and it forges creative novel connections.

In total for a single night, there’s about an 80/20 split between NREM/REM sleep.

When you sleep, your brain goes through sleep cycles that each last about 90 minutes. Each sleep cycle generally begins with NREM sleep, then ends with REM sleep. As one cycle ends, the next begins. You can see this in a sleep graph here:

A deeper line means going deeper into NREM sleep.

How Sleep Cycles Change Through the Night

- Notice that not all sleep cycles look the same. As the sleep progresses through the night, a greater fraction of each cycle is spent in REM sleep.

- Why would the sleep cycles be unbalanced in this way? Why not just have all sleep cycles look the same, with 80% in NREM and 20% in REM?

- The author hypothesizes that it’s like making a sculpture out of a mass of clay. Earlier in the night, more NREM is needed to clear out junk memories that aren’t useful anymore. Then once only the useful stuff remains, REM strengthens what’s left.

- One way to think about this is that an animal might be interrupted in the middle of the night. So if an animal could only sleep 3 hours in one night, it’d make sense for the more critical functions to be performed first, with the later functions being a luxury if the animal could sleep a full night. This may suggest that NREM performs a more vital function for survival

- Also, beware of what this means for cutting your sleep short. If you normally sleep 8 hours, and one night you have to cut sleep to 6 hours, then you’re not just losing 25% of sleep - you might be losing 60-90% of your REM sleep!

- Likewise, going to sleep later than usual might cut short your NREM sleep.

What REM and NREM Look Like

- REM and NREM are distinguishable by measuring electrical activity in the brain. NREM is characterized by slow (3-4 Hz) waves that propagate far from the frontal cortex to the back of the brain. REM is characterized by faster (30-40 Hz), frenetic activity that looks the same as being awake.

- Wakeful thought looks frenetic because many different neural signals are occurring at once throughout the brain. An analogy: it’s like a microphone picking up a football stadium full of distinct conversations. The summation of all the conversations just looks like noise.

- In contrast, NREM sleep is a slow, pulsing wave that’s noticeably different from REM sleep. Continuing the analogy, it’s like a stadium full of voices singing in synchronization. That billions of neurons can do this together is awe-inspiring.

- What’s the function of these slow NREM waves? By being lower frequency, slow NREM waves can propagate further without attenuation, like AM radio waves. The author suggests this is useful in transferring memories far across the brain, from temporary memory stores toward more permanent storage. It also allows communication across the brain for different sections to collaborate on their shared experience.

- REM sleep looks like awake activity, and it’s where dreams happen. A few odd things happen during REM sleep:

- Your sense of time in dreams seems dilated - an hour may seem to pass when in reality only 5 minutes have.

- Unlike the rest of sleep, you consciously perceive your senses, like sight and sound. In non-REM sleep, the [[thalamus]] in your brain blocks you from consciously perceiving senses. Once REM sleep starts, this blockade is released.

- In REM sleep, your eyes move rapidly This was initially thought to be visual exploration of the dream field, but this turns out to be more related to the creation of REM sleep than passive observation of it.

- If REM sleep looks like wakefulness, how can an observer distinguish someone who’s dreaming from being awake?

- Muscle atonia : during REM sleep, your voluntary muscles are completely limp. Your brain does this to prevent you from acting out your dreams, since fighting an enemy might cause you to accidentally punch your surroundings.

- One last detail: sleep spindles (bursts of activity) occur at the end of slow waves, possibly serving a function to block external sensory input from disrupting sleep. People with more sleep spindles are heavier sleepers.

Chapter 4: Interesting Facts About Sleep

Sleep in Animals

- Sleep is present in all animal species, even invertebrates. And bacteria that survive for longer than 24 hours have circadian-like rhythms. As we’ve said before, this suggests that it’s universally critical for survival.

- We ask all the time why we sleep. One researcher posed an interesting inversion of the question - if wakefulness is damaging to the body and sleep recovers it, why did life ever bother to wake up? (of course, you can’t be productive and reproduce when sleeping, so sleeping too much would be evolutionarily disadvantageous.)

- The amount of sleep per day varies from 4 hours in elephants to 19 hours in bats. There are no strong correlations between animal characteristics and amount of sleep, though within animals of a similar size, a more complex brain increases sleep.

- Among animals, REM sleep occurs only in birds and mammals. Because REM evolved independently in these two distant evolutionary trees, REM likely performs a critical function that NREM cannot accomplish, or that REM is more efficient at accomplishing.

Interesting animal sleep patterns

- Cetaceans (dolphins, whales) sleep with half their brain at a time. They also don’t have REM sleep (as formally defined), since the muscle atonia would prevent swimming. But they may have some variant of REM that’s harder for researchers to detect.

- Birds in a flock will have most birds in full-brain sleep, then birds in the perimeter sleeping with half their brains to stay alert for danger

- Similarly, humans in a new environment (like a new hotel room) show one half of the brain sleeping lighter than the other half, like it’s staying alert to detect danger. This is why the first night in a new environment can be so unrestful. As you acclimate to the environment, this half-brain sleep dissipates.

- Transoceanic birds that cross thousands of miles have ultra power naps, sleeping for seconds at a time.

Sleep in Humans

- What’s the ideal human sleep pattern?

- Native pre-industrial tribes show a biphasic sleep pattern, with 7-8 hours at night and a 30-60 minute nap in the afternoon. At night, they sleep 2-3 hours after sunset, awaking around dawn.

- All people tend to have a dip in energy in mid-afternoon. (So if you’re scheduling a presentation, avoid the slot right after lunch.)

- A study of Greek siestas showed that people who abandoned [[siesta]]s (due to political and social pressure) showed a** 37% increase risk of death from heart disease** compared to those who maintained siestas.

- What about supposed historical styles of sleeping, like segmented sleep (two periods of sleep at night, separated by a few hours of wakefulness)? The author argues this is mostly a cultural artifact, and not a natural way to sleep. No evidence suggests a biological desire to wake up for a few hours in the middle of the night

- Relative to great apes, humans sleep less (8 hours in humans vs 10-15 hours in apes) and have more intense REM sleep (20% in humans vs 9% in apes). Matthew Walker hypothesizes this evolved as follows:

- Apes sleep in trees and enjoy great safety at night.

- In the human ancestor [[Homo erectus]], an upright body posture and shorter arms made sleeping in trees more difficult. REM sleep is also dangerous in trees because limp muscles increases the risk of falling out.

- Discovery of fire allowed humans to ward off predators and parasites at night. But danger still inevitably lurked, so humans who could sleep more efficiently for less time were evolutionarily selected for.

- Then as human societies became more complex, REM sleep became more important. REM sleep is found to be critical for

- internal emotion regulation

- reading emotions from others

- creativity.

- This led to improved survival strategies and larger social groups, which further increased brain complexity and more need for REM sleep, forming a positive feedback loop.

Chapter 5: How Sleep Changes from Childhood to Adulthood

Babies

- Fetuses spend almost all of the time in a sleep-like state. It doesn’t yet have the part of the brain that causes muscle-atonia during sleep, thus explaining why babies in the womb kick and punch.

- During the last 2 weeks of pregnancy, REM sleep in fetuses ramps up to 12 hours a day. This causes rapid synaptogenesis and building of neural pathways throughout the brain. In experiments with rat fetuses, disturbing REM sleep stalls construction of the cerebral cortex.

- Alcohol impedes REM sleep in fetuses and babies, causing abnormal synaptogenesis. Once disrupted, a fetal brain may never fully regain normal function.

- Newborns of alcoholic mothers spend far less time in REM sleep.

- 2 drinks reduce REM sleep and breathing rate in unborn infants.

- When babies drink milk containing alcohol, their REM sleep reduces by 30%.

- Because REM sleep is involved in emotional recognition and social interaction, disrupting REM sleep in utero might contribute to the autism spectrum.

- Autistic people show 30-50% less REM sleep than normal.

- Rats deprived of REM sleep develop into socially withdrawn adults.

Childhood

- While starting with very irregular sleep, babies eventually show more regular sleep patterns starting at 4 months, as their suprachiasmatic nucleus and circadian rhythm develop.

- With age, total time sleeping decreases, and the fraction of REM sleep decreases. Now that the synaptogenesis of REM tapers off, NREM plays a larger role in brain refinement, pruning the associations that are most valuable unique to that child’s life.

- Consider NREM to actually cause cognitive development - changes in deep NREM sleep precede cognitive milestones, and the last maturation is in the frontal lobe, dealing with rationality.

- Caffeine exposure during childhood could reduce NREM sleep, delaying brain maturation and learning.

Teens

- In puberty, teens develop a later biological clock than adults, preferring to stay up later and wake later. This isn’t just teens being rebellious - it’s in their biological nature. Asking teens to sleep at 10PM is like asking adults to sleep at 7PM.

- The author theorizes that this is evolutionarily helpful for teens to gain independence from their parents (having time to be awake while their parents are sleeping). Moreover, teens do so collectively, and so they get private time to socialize.

- Unfortunately, in the modern day, schools start at a very early hour (largely to match the circadian rhythms of adult parents). It’s far out of sync with the natural circadian rhythm of teens, so they tend to sleep late and wake up far earlier than they naturally would.

- Considering all this, if you’re a parent, there’s no need to get frustrated at your teenage kid for seemingly being lazy and sleeping too much, when the environment is heavily geared against their biological tendencies.

Adulthood/Old Age

- Sleep quality starts deteriorating in the late 20s, with deep NREM sleep becoming impaired in length and power. In your late 40s, you’ll have lost 70% of deep sleep as a teenager; by 70, you’ll have lost 90% of deep sleep. Unfortunately, less NREM sleep worsens the ability to cement new memories in older people.

- You often hear of the elderly sleeping little at night, so the natural conclusion is that the elderly just need less sleep. But this could be a myth. The elderly might be sleeping less because they’re unable to sleep for as long. This means they could still benefit from more sleep.

- Seniors have three things going against them: 1) they sleep less, 2) they have less efficient sleep, and 3) they want to sleep earlier. This is caused by:

- Degeneration of the mid-frontal cortex that generates sleep

- Circadian rhythm shifting to earlier times

- Weakened bladders causing night interruptions

- Exacerbating this are a few factors:

- We’re generally unable to determine our sleep quality after sleeping. So when seniors sleep poorly and feel unhealthy, they don’t realize they need to improve their sleep quality. They chalk it up to insomnia.

- Because the elderly sleep poorly, they feel tired during the day, and they doze off in the early evening. Unfortunately, this reduces the adenosine sleep pressure at night, which causes them to have trouble falling asleep later. Then, their early circadian rhythm wakes them up before they can get a full night’s rest. This causes a vicious cycle of poor sleep.

- All this causes lower sleep efficiency - people in their 70s have 80% sleep efficiency, meaning they stay awake in bed for 1.5 hours when trying to sleep 8.

- There are a few ways to get around this:

- Melatonin helps strengthen the desire to sleep in elderly people. It reduces time to falling asleep and improves reported sleep quality.

- Seniors who want to push their circadian rhythm back should get bright-light exposure in the late afternoon, not in the mornings.

Chapter 6: How Sleep Benefits the Brain

Getting good sleep improves your brain in these ways:

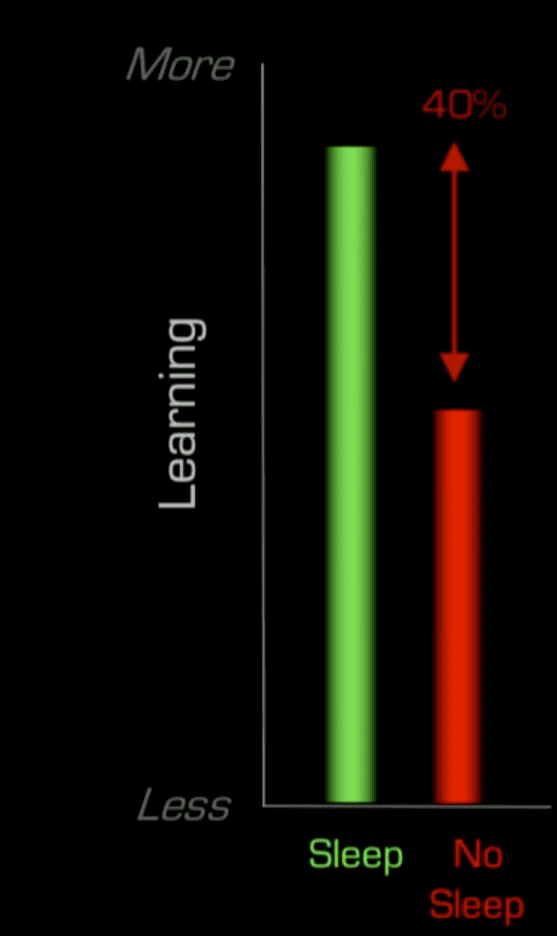

1. Sleep improves long-term factual recall

- Your brain stories different memories in different places. The hippocampus stores short-term memory with a limited capacity; the cortex stores long-term memory in a large storage bank.

- The slow-wave, pulsating NREM sleep moves facts from the [[hippocampus]] to the cortex. This has two positive effects:

- it secure memories for the long term

- it clears out short-term memory to make room for new information and improves future learning.

- Have you ever woken up recalling facts that you couldn’t have recalled before sleeping? Sleep may make corrupted memories accessible again.

- While good sleep improves memory, sleep deprivation can prevent new memories from being formed. In part, this might be because the hippocampus becomes less functional with less sleep, partially because lack of NREM sleep prevents solidifying of new memories.

- Unfortunately, making up a sleep deficit later doesn’t help recover a previous days’ memory - if you lost it, you’ve lost it.

2. Sleep prunes memories worth forgetting

- Sleep doesn’t preserve all memories equally strongly - somehow, the brain knows which memories are useful and worth preserving, and which ones are useless and OK discarding.

- Experimentally, this has been shown in experiments where subjects are given a list of words and instructed which words to remember and which to forget. Students who get to take a nap show stronger memories for the appropriate words, compared to students who don’t nap.

3. Sleep increases “muscle memory” or motor task proficiency

You might struggle with a motor task (like playing a tough sequence on piano), but after sleeping, be able to play it flawlessly. Sleep seems to transfer motor memories to subconscious habits.

Sleep deprivation also worsens general athletic performance: getting less sleep decreases your aerobic capacity, time to exhaustion, and recovery; and it increases the risk of injury and lactic acid generation.

The above benefits generally occur in NREM sleep, which is concentrated in the beginning of sleep. In experiments, participants who have NREM sleep disrupted perform worse than those who have REM sleep disrupted.

A few last scientific details:

- Motor memory is associated with stage 2 NREM, which is concentrated in the last cycle of sleep.

- Sleep spindles are associated with better memory effects.

Now that we understand the impact of sleep on the brain, imagine how we can apply this knowledge into useful therapies:

- Imagine modifying sleep to selectively control what to remember from the day - like remembering content for an upcoming test and a happy moment, while decreasing traumatic moments. (This might lead to the side effect of having a have distorted memory of life).

- Use sleep to delete traumatic memories (for PTSD) or train away bad motor habits (like substance abuse).

- Find ways to augment the natural abilities of sleep, like with electrode stimulation of brain, pulsing sound in sync with brain waves, or rocking the bed rhythmically.

Chapter 7: How Sleep Deprivation Harms the Brain

- While getting great sleep is good for the brain, sleep deprivation is unambiguously harmful to the brain. We’ll show damage in three ways: to attention, to emotion control, and for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Sleep Deprivation Worsens Attention and Concentration

- Sleep deficits are very bad for attention and concentration. This is especially harmful during high-risk activities, like driving.

- Here are some ways to put the risk into perspective:

- Driving after having slept less than 4 hours increases crash risk by 11.5x.

- Being awake for 19 hours (being past your bedtime by 3 hours) is as cognitively impairing as being legally drunk.

- Adding alcohol to sleep deficits has a multiplicative effect on mistakes, not just an additive one.

- Sleep deficits add up over time, and performance progressively worsens with greater sleep deficit. Having 10 nights of 6-hour sleep is equal in damage to one all-nighter, as is 6 nights of 4-hour sleep.

- Why does sleep cause more accidents? Part of it is delayed reaction time. Another part is a “microsleep,” where your eyelids shut for just a few seconds and you go unconscious and lose motor control. If you’re in a car going 60 mph, falling asleep for just a few seconds could result in a terrible accident.

- Sleep deprivation is an insidious problem because when you’re sleep-deprived, you don’t know how poorly you’re performing. (This is like being drunk and thinking you’re far more capable of doing things than you actually are). And if you’re chronically sleep-deprived, your low performance becomes a new normal baseline, so it’s hard for you to see just how badly you’re performing.

- Think you can do just fine on 6 hours of sleep? Chances are, you can’t. Less than 1% of the population is able to get six hours of sleep and show no impairment (this is largely genetic and relates to the BHLHE41 gene). Everyone else is just fooling themselves and propping up their energy with caffeine.

- And think you can get by with power naps? They only get you partway there - power naps are most effective at the onset of fatigue, not when you’re already sleep-deprived.

Sleep Deprivation Worsens Emotional Control

- A baby that doesn’t get its nap time tends to get cranky. Adults are the same way.

- The [[amygdala]] is the part of your brain responsible for emotions like fear and anxiety. Normally, it’s held in check by your prefrontal cortex (the rational part of your brain). But when you’re sleep-deprived, this suppression is weakened, and your amygdala can [[run amok]], leading to 60% more emotional reactivity. The highs can be higher, and the lows lower.

- On the other side of fear and anxiety, positive rewards and dopamine may be amplified by sleep deprivation too. Therefore, sleep deprivation can intensify sensation-seeking, risk-taking, and addiction.

- More gravely, sleep may play an important role in mental illness. Here’s suggestive evidence:

- Sleep disruption is a common symptom of all mood disorders. The causation is unclear: does bad sleep cause mood disorders, or do mood disorders cause bad sleep, or both? But the author believes sleep plays at least some aggravating role.

- One night of sleep deprivation can trigger a manic or depressive episode in bipolar patients.

- Sleep deprivation is associated with suicidal ideation in teenagers.

- Surprisingly, sleep deprivation makes ⅓ of depression patients feel better, possibly by amplifying their positive emotions. However, it makes ⅔ feel worse, so it isn’t prescribed as a treatment.

Sleep Deprivation May Contribute to Alzheimer’s

- While no definitive causal link has been shown yet, sleep losses may contribute to Alzheimer’s through a few mechanisms:

- Frontal lobe degeneration (especially through Alzheimer’s characteristic amyloid plaques) disrupts NREM sleep.

- Lack of NREM sleep disrupts memory formation, a key symptom of Alzheimer’s. (Notably, the hippocampus is not affected by amyloid plaques, presenting a conundrum to scientists on why memory is disrupted in Alzheimer’s.)

- Lack of NREM sleep disrupts the lymphatic cleanup system, during which glia shrink to less than half their normal size and amyloid plaques are cleared out more readily.

- It’s easy to see how a vicious cycle can occur - frontal lobe degeneration disrupts NREM sleep, which causes further frontal lobe degeneration.

- Sleep loss precedes Alzheimer’s by several years, suggesting this could be an early diagnostic.

- Encouraging NREM sleep, through artificial brain stimulation if needed, might be therapeutic for Alzheimer’s. It could also be prophylactic, the same way statins protect against heart disease.

Chapter 8: How Sleep Deprivation Harms the Body

- In addition to the damage it causes to the brain, sleep deprivation disrupts the normal function of many physiological processes, likely contributing to chronic diseases. In this chapter, we’ll cover a bevy of health issues associated with sleep deprivation.

- At a high level, sleep deprivation of even just 1-2 hours triggers the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight response) and disrupts hormonal balances. This also implies that sleep is necessary for the normal maintenance of physiology.

A Caveat

- Many of the population studies cited in Why We Sleep are correlational - e.g. people who sleep less are more likely to have heart disease, after controlling for many other factors. But the causation is unclear - some other factors that predispose people to get heart disease (like a high baseline level of stress) could also reduce sleep.

- To address this, the experimental studies cited attempt to link lack of sleep to a middle physiological state, which itself is causative for the disease. For instance, lack of sleep increases blood pressure, which the medical consensus believes is causative for heart disease.

- Ideally, the “smoking gun” experiment would be to randomize people into normal-sleep and low-sleep groups for years, then observe the rate of disease. However, this is impractical (it’s hard to run very long studies like this and impossible to double-blind) and likely unethical (if low sleep is already believed to cause severe disease).

Diseases and Sleep Deprivation

- Heart Disease

- Sleep deprivation has a number of effects related to cardiovascular disease:

- It activates the sympathetic nervous system, leading to

- Increased heart rate

- Increased vasoconstriction -> increased blood pressure

- Increased cortisol (stress hormone)

- Increased atherosclerosis (esp of coronary arteries)

- Through hormone signaling, it decreases HDL (good cholesterol) and growth hormone (promotes recovery of blood vessel endothelium)

- A population study showed that shorter sleep was associated with a 45% increased risk of developing heart disease.

- An interesting finding: daylight savings time is a natural sleep experiment that typically increases or decreases sleep by 1 hour. When the clock moves forward and the population gets 1 less hour of sleep, there is a [significant spike in heart attacks] and traffic accidents.

- Diabetes

- Sleep deprivation reduces insulin responsiveness, which causes hyperglycemia.

- In an experiment, after 4 hours of sleep a night for 6 nights, subjects were 40% less effective at absorbing a standard dose of glucose.

- In a population study, those sleeping <6 hours a night showed higher rates of T2D (after controlling for body weight, alcohol, smoking, and other factors).

- Sleep deprivation reduces insulin responsiveness, which causes hyperglycemia.

- Obesity, Weight Gain

- As it relates to weight, sleep deprivation:

- Hormonally, reduces leptin (the hormone that makes you feel full) and increases ghrelin (the hormone makes you feel hungry). It becomes harder to feel satisfied after eating.

- Increases endocannabinoids (reduces pain sensation but increases appetite; also released in runner’s high), which increases eating

- Makes you feel lethargic, which makes you less likely to exercise

- Disrupts the linkage between the rational prefrontal cortex and the primal appetite center in the brain (similar to emotional control in the last chapter), so it becomes harder to regulate your eating

- In an experiment, subjects were randomized into a normal 8-hr sleep group, and a low 4-hr sleep group. Both groups were carefully monitored and controlled for physical activity.

- The low-sleep group ate 300 more calories each day, even after just 4 days of sleep deprivation.

- The low-sleep group was also more prone to overeating each meal, consuming 330 more calories in snack foods after a meal.

- One might argue that decreased sleep naturally causes more calorie burn, but an all-nighter actually consumes only 147 more calories than sleeping. Sleep is metabolically more intense than you might guess.

- Finally, if you’re losing weight and under sleep deprivation, the shift of where you lose the weight from differs. When sleep-deprived, 70% of weight loss comes from lean body mass like muscles, compared to under 50% with plentiful sleep.

- As it relates to weight, sleep deprivation:

- Reproductive System

- In males, sleep deprivation decreases testosterone, testicle size, and sperm count.

- Experimentally, the is acute - 5 hours of sleep for one week “ages” a man 10-15 years by testosterone

- Beyond libido, testosterone also governs bone density and muscle mass.

- In females, sleep deprivation reduces follicular-releasing hormone (necessary for conception), increases abnormal menstrual cycles, and causes more issues with infertility.

- Your face is rated as less attractive and less healthy after one night of short sleep. So there might be something to the idea of “beauty sleep.”

- In males, sleep deprivation decreases testosterone, testicle size, and sperm count.

- Immune System

- Sleep deprivation reduces your ability to ward off infectious disease:

- In an experiment, subjects exposed to low sleep over 1 week were 50% likely to develop a cold when exposed to a virus, vs 18% in the normal-sleep group.

- Sleep deprivation reduces the immune response to flu vaccines by over 50%.

- Sleep deprivation reduces circulating levels of natural killer cells .

- Sleep deprivation reduces your ability to ward off infectious disease:

- Cancer

- Sleep deprivation increases inflammation, which increases cancer severity:

- Promotes angiogenesis, or blood vessel development

- Promotes lability of cancer cells, leading to metastasis

- Downregulates M1 macrophages and upregulates M2 macrophages, both changes increasing cancer risk.

- Experimental evidence:

- Experiments in mice show an increase in speed and size of cancer growth under sleep deprivation.

- Population studies show a link between nighttime shift work and risk of cancer (common occupations include nurses and pilots).

- In response, Denmark now pays worker comp to women who developed breast cancer after doing night-shift work in government-sponsored jobs

- Sleep deprivation increases inflammation, which increases cancer severity:

- Aging

- Telomeres are a component of DNA, and they get shorter with aging. Sleep deprivation has been shown to hasten telomere shortening, thus implying an increase in aging.

- Why would animals evolve so that sleep deprivation causes all these bad issues? Evolutionarily, consider that these responses might promote survival: in caveman days, times of low sleep may mean conditions that threaten survival (low food stores, tough weather, hostility with another tribe). The above responses might promote short-term survival-hoarding calories, activating the “fight-or-flight” system, decreasing reproduction - at the expense of long-term well-being. #[[进化论]]

Chapters 9-11 The Benefits of Dreaming

- Dreaming is a bizarre sensation. You’re unconscious, but you perceive intense vivid sensations and hallucinate things that aren’t there. You feel like you’re moving in the world, but your muscles have been forced to be limp. You remember faces and memories that you haven’t thought about for years, maybe decades. You had no control over your emotions, swinging from intense rage and jealousy to exuberance. Finally, when you woke up, you promptly forgot everything. If you experienced all of this while awake, you’d think you had a psychosis episode!

- It’s not surprising then that dreaming has had a complicated history. In the ancient past, Egyptians and Greeks wondered if dreams were divine gifts from gods.

- Freud helped dispel this, firmly centering it within the human brain. He considered dreams as expressions of repressed desires, and he built a psychological movement around interpreting dreams as such.

- The critical flaw in Freudian analysis was its unprovability - the interpretation methods were so subjective that different approaches yielded different results, and there was no strict hypothesis that was testable.

- Furthermore, the interpretations were as vague as horoscopes, thus seeming full of significance but not providing any practical insight (like “your dream is reminding you of how little time you have to do all the things you want to do.” Pretty much everyone feels this way.)

The Science of Dreaming

- Most vivid dreaming happens during REM sleep (though NREM sleep has some vague non-vivid dreaming, like “I was thinking about clouds”).

- During REM dreaming, your visual, motor, memory, and emotional areas of the brain are active. Your prefrontal cortex (governing rationality) is muted.

- Interesting: it may be possible to predict what you’re dreaming about through fMRI.

- To build a profile of your brain, you look at different images while awake, and the fMRI signature is captured.

- Then as you dream, your dreaming fMRI is matched to your awake fMRI profiles, predicting what you’re currently looking at while dreaming.

- We often think about the meanings of our dreams. Do dreams merely replay events of the day, or do they reflect our emotional concerns?

- A study showed that only a small fraction (1-2%) of dreams replay the literal events of the day.

- A greater fraction of dreams (~45%) reflect our underlying emotional worries we have while awake.

We’ll now discuss three benefits of dreaming and REM sleep.

REM Sleep Blunts Emotional Pain from Memories

- REM dreaming reduces pain from difficult emotional experiences. The brain seems to reprocess upsetting memories and emotional themes, retaining the useful lessons while blunting the visceral emotional pain. This might be why we can look back at painful memories without feeling the original full emotional intensity.

- Interestingly, dreaming about the upsetting content itself, or its emotional themes, is necessary to have this emotional blunting effect. REM sleep by itself does not.

- How might this happen? In REM sleep, the stress hormone norepinephrine in your brain is reduced to zero, which possibly allows the brain to process upsetting memories in a “safe” brain environment. In fact, REM sleep is the only time that norepinephrine is absent from your brain.

- Suggestive evidence:

- PTSD patients have elevated norepinephrine in REM sleep. They also have recurring nightmares where the pain of the memory does not fade, either dreaming or wake.

- Reducing norepinephrine levels through a drug reduces PTSD severity in a subset of patients.

- In an experiment, subjects were shown a series of emotionally triggering images two separate times, separated by ~12 hours. One group saw set 1 before sleeping and set 2 after sleeping. The other group saw both on the same day without sleeping, set 1 in the morning and set 2 at night. The former group reported much less emotional disturbance upon seeing the images the second time, suggesting sleep had blunted their emotional reaction.

- PTSD patients have elevated norepinephrine in REM sleep. They also have recurring nightmares where the pain of the memory does not fade, either dreaming or wake.

REM Sleep Increases Understanding of Other People’s Emotions

- Sleep deprivation reduces your ability to interpret subtle facial expressions. Sleep-deprived people more often interpret faces as hostile and aggressive.

- Suggestive evidence: people on the autism spectrum have disrupted REM sleep. They also have issues reading people’s facial expressions

- This function seems to begin in adolescence, when kids have to start navigating the social world independently.

- Imagine the mistakes sleep-deprived professionals can make - police, medical staff, parents - if they mistake faces for aggression.

REM Sleep Increases Creativity

- REM sleep creates novel associations between ideas, increasing creativity and problem-solving.

- Informally, imagine the brain asking: “how can I connect what I’ve recently learned with what I already know, thus discovering insightful revelations? What have I done in the past that might be useful in solving this new problem?”

- Thomas Edison knew the power of dreams. Reportedly, he would fall asleep holding metal ball bearings, releasing them just as he entered REM sleep. The noise would wake him up, just in time for him to write down his dreams before he forgot them.

- These experiments showed a bevy of positive effects on creativity:

- REM sleep creates novel connections, between distantly related concepts

- In essence, the brain takes and builds a larger mental network of separate ideas. For example, you learn A->B and B->C separately, and the brain forms the larger relationships A->B->C.

- In this way, your brain connects new experiences to old ones. If you have to solve a problem today, you might think back to a similar problem you solved on vacation 5 years ago.

- REM sleep creates higher-level comprehension of ideas, finding the patterns among the noise

- Examples: language learning as a child, finding shortcuts for solving repetitive math problems

- REM sleep increases the ability to solve creative problems

- In an experiment, subjects in sleep were woken up to solve anagrams (eg OEOSG = GOOSE). Those waking up from REM sleep solved 15-35% more puzzles than those in NREM sleep or while awake.

- The content of REM sleep matters when solving that problem

- In an experiment, subjects were given a maze to solve and given a chance to nap. People who dreamt about issues related to mazes were 10x better at solving the maze upon waking, vs people who didn’t dream about mazes.

- The book cites Mendeleev, the chemist who developed the breakthrough periodic table of elements. He reported happening upon the solution in a dream

- REM sleep creates novel connections, between distantly related concepts

Lucid Dreaming

- Lucid dreamers are able to voluntarily control their actions during dreaming.

- Lucid dreaming is real. Researchers can verify when someone is lucid dreaming by pre-arranging eye movements and hand signals while awake, then detecting it while the person is sleeping (the hand signals are detected by fMRI - remember, you can’t move during REM sleep because of muscle atonia).

- Less than 20% of people in the population are capable of lucid dreaming, suggesting it might not be a hugely advantageous capability. But it sure sounds fun.

Chapter 12: Sleep Disorders

- We’ve talked before about how sleep deprivation causes disease. Now we’ll discuss sleep disorders, or primary issues with abnormal sleep, and their consequences.

Somnambulism / Sleepwalking

- Sleepwalking is the act of walking and performing other behaviors while asleep. Automatic, nonconscious routines are executed, like brushing teeth or opening the refrigerator.

- Sleepwalking happens during NREM sleep, and not REM dreaming sleep (like some think). Neurologically, sleepwalking is accompanied by an unexpected spike in nervous system activity, causing the person to be stuck somewhere between sleep and wakefulness.

- Sleepwalking is more common in children than adults, for unknown reasons - possibly because kids spend more time in NREM sleep than adults do.

- In one of the most extreme cases, a sleepwalker drove 14 miles to an in-laws’ home, stabbed the mother-in-law to death, and strangled the father-in-law (who survived). This person was later acquitted as not being control of his actions. This defense has been tried in later cases (most unsuccessfully).

Insomnia

- Insomnia is defined as making enough time for sleeping, but having insufficient sleep quantity or quality, for more than 3 months. Symptoms include difficulty falling asleep, waking up in the middle of the night, and feeling unrefreshed in the morning.

- When they do sleep, insomniacs have more fragmented REM sleep and shallower brainwaves in NREM.

- 1 out of 9 people suffers from insomnia. It’s twice as common in women than men, and more common in blacks/Hispanics than whites, for unknown reasons.

- The most common triggers of insomnia are emotional concerns or distress. The biological cause is linked to an overactive sympathetic nervous system, which raises body temperature and levels of cortisol/epinephrine. In turn, the thalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala all remain more active than in normal sleeping patients

- Given the complex physiology of insomnia, it’s unlikely blunt instruments like sleeping pills will fix the root cause.

Narcolepsy

- People with narcolepsy show sudden bouts of extreme sleepiness during the day. Some people who are chronically sleep-deprived mistakenly think they’re narcoleptic. The severity of feeling for narcolepsy is far more severe, equivalent to the feeling after 3 consecutive all-nighters. Narcolepsy occurs in just 1 out of 2,000 people

- Narcoleptics also suffer other symptoms:

- Sleep paralysis (waking up in REM sleep during muscle atonia), accompanied by a feeling of dread (which comes from being unable to move in response to a possible threat).

- Many UFO sightings are attributed to sleep paralysis

- Cataplexy (sudden loss of muscle control while awake)

- In cataplexy, patients aren’t asleep – they’re fully active but paralyzed.

- These are triggered by strong emotional reactions, both positive and negative (jokes, surprise, a nice shower, playing with kids, a horn when driving)

- To avoid any triggering events, narcoleptics isolate themselves emotionally to avoid cataplexy

- Sleep paralysis (waking up in REM sleep during muscle atonia), accompanied by a feeling of dread (which comes from being unable to move in response to a possible threat).

- How does narcolepsy arise? It’s a disruption in a normal process. Normally, wakefulness is signaled by the neurotransmitter orexin in the hypothalamus; in sleep, this is shut off.

- In narcoleptic patients, 90% of orexin-secreting cells are destroyed, and orexin receptors are downregulated.

- This insufficient signaling causes the body to exist in a “not-awake not-asleep purgatory” throughout the day and night.

- There are no current effective treatments for narcolepsy.

- Amphetamine/Provigil is used for daytime sleepiness

- Antidepressants suppress REM sleep, which helps with sleep paralysis and cataplexy

- New drugs like suvorexant (meant to block orexin at night) caused patients to fall asleep just 6 minutes faster.

Sleep Deprivation and Death

- Gravely, sleep deprivation can directly cause death.

- In rodent studies, REM sleep deprivation causes death over the same period as food deprivation - about 15 days.

- NREM sleep deprivation causes death too, after 45 days.

- Sleep-deprived rats lose body weight, despite eating more. They can no longer regulate their body temperature, causing intense metabolism.

- The immune system is destroyed, causing widespread skin sores.

- The cause of death is universally septicemia or a systemic bacterial infection, caused by the gut microbiome (normally held in check by a functioning immune system).

- In humans, sleep deprivation leading to death is uncommon (possibly since the natural urge to sleep is so strong). But lack of sleep could contribute to more acute causes of death like seizures, and thus be misreported.

- The strongest evidence that humans can die from sleep deprivation comes with a very rare inherited condition, fatal familial insomnia. In this disease, prion proteins cause the thalamus to be destroyed, and the patient is totally unable to sleep, even with heavy sedatives. Severe disability sets in (dementia, speech disorders), and death occurs within 10 months. There are no treatments or preventions.

- This disease is autosomal dominant and found in only 40 families worldwide.

- In rodent studies, REM sleep deprivation causes death over the same period as food deprivation - about 15 days.

So how much sleep should we get?

- Let’s return to the question of normal sleep amounts.

- On the lower end, you may have seen reports of hunter-gatherer tribes who sleep just 6.5 hours, leading to assertions that this is a universally “natural” state for all humans. They also are rarely obese.

- But this is a misguided conclusion. In reality, the hunter-gatherer tribes are basically perpetually starving, since food is never abundant for long periods of time. Starvation naturally induces less sleep, so that animals stay awake longer to search for food. (This also decreases obesity).

- To wit, the average life span is just 58 years, much shorter than humans in industrialized societies. In nutrition-rich situations, most humans need 8 hours of sleep.

- Can you sleep too much?

- Some population studies show increased risk of death when sleeping over 9 hours, suggesting sleeping too much might be harmful. But the author argues this data is confounded by infection and cancers in long-sleeping people [though these confounds should already have been controlled for].

- Matthew Walker argues there is no evidence that sleeping more causes any health defects

- Some population studies show increased risk of death when sleeping over 9 hours, suggesting sleeping too much might be harmful. But the author argues this data is confounded by infection and cancers in long-sleeping people [though these confounds should already have been controlled for].

Chapter 13: What Stops You From Getting Good Sleep

- Five influences have drastically changed how we sleep: caffeine, light, temperature, alcohol, and alarms.

Caffeine

- This was already discussed in chapter 2. The tips, for good measure:

- Caffeine is of course in coffee, some soft drinks, and some teas, but also chocolate.

- Be careful when drinking decaf, as it apparently contains 15-30% of the caffeine in regular coffee - it’s nowhere near zero caffeine.

- If you must have it, don’t drink it in the afternoon, and definitely not in the hours before sleep.

Light

- Light is a signal for the suprachiasmatic nucleus to regulate the circadian rhythm (by signaling to the pineal gland to secrete melatonin). In the natural world, when the sun goes down, there’s little light. But nowadays, artificial light bathes our homes and disrupts our circadian rhythm.

- Any light is disruptive to the circadian rhythm. Electric light delays your 24-hour circadian rhythm by 2-3 hours each evening.

- Even 8-10 lux (a measure of light intensity) delays melatonin release. A bedside lamp is 20-80 lux, and a typical living room is 200 lux, suppressing melatonin by 50%. (In comparison, the full moon only provides about 0.1 lux.)

- Light can suppress melatonin for days after usage stops.

- *Blue light is most problematic**, suppressing melatonin at twice the levels of warm light. Blue light is most strongly emitted by digital screens like TVs, computer monitors, and smartphones.

- We respond most to blue light because we evolved from marine creatures, and blue light penetrates water best. #[[进化论]]

- Reading on an iPad vs a book causes 50% less melatonin secretion and delayed the rise by 3 hours.

- Tips:

- Dim lights in the rooms where you spend evenings.

- Maintain complete darkness throughout the night, using blackout curtains.

- Use settings on your phone and computers to tint the screen orange, reducing blue light.

- Consider yellow-tinted glasses that block blue light.

Constant temperature

- In natural environments, the temperature rises and falls with the day. This is used by the hypothalamus, along with light, to set the circadian rhythm. Our bodies react in kind – before sleep, the body cools, ejecting heat through densely perfused areas like hands, feet, and face.

- But in modern days, we use thermostats to homogenize our temperatures, suppressing the highs in the day and raising the lows with pajamas and blankets. Our brain doesn’t get the same signal about the day’s cycle that it used to.

- Cooling body temperatures improves sleep. In an experimental treatment, people wear a bodysuit that circulates cool water. Among insomniacs and the elderly, this reduces time to sleep and increases the quality of NREM sleep.

- Tips:

- The best temperature to sleep at with standard bedding and clothing is 65F, which is far lower than most people keep bedrooms.

- Try activities that help remove heat from the body:

- Hot bath before bed (expands capillaries, which after bath drops temperature)

- Splashing water on your skin

- Sticking your hands and feet outside the blanket

Alcohol

- Alcohol is a sedative, causing what appears to be sleep but is really more like anesthesia. It disrupts sleep by suppressing REM sleep and causing waking throughout the night. This is caused by aldehydes from alcohol metabolism.

- Alcoholics are so sleep-deprived that their brain imposes REM-like behavior during wakefulness, such as hallucinations and scattered thinking. (Shortform note: an unfortunate vicious cycle can result here – alcohol disrupts sleep, which causes more fatigue and less behavior control when awake, which prompts more alcohol.)

- By disrupting REM sleep, alcohol disrupts the normal processes of learning and complex knowledge.

- In an experiment, subjects were tasked with learning a new grammar on day 1. When exposed to alcohol on the first night, they lost 50% of memory recall compared to the abstinent group. Surprisingly, those getting alcohol on night 3 lost 40% - damage can occur for memories days past.

- Tips:

- The author encourages total abstinence from alcohol, as puritanical as that sounds. A drink takes hours to fully degrade and excrete, and it’s even worse for people with alcohol flush reactions.

Alarms

- Alarms cause acute stress responses when you wake up, spiking cortisol, heart rate, and blood pressure. This is not good for you. Even worse, snoozing the alarm causes multiple stress responses in quick succession.

- *The best path to waking is natural, without alarms.** Wake up at the same time of day every day. If you have to, commit to waking up when you hear the alarm, to avoid snoozing.

- “Life hacks” on how to defeat the snooze button are missing the point - rearrange your sleep so you wake up naturally.

Chapter 14: How to Get Better Sleep

Good Sleep Practices, Continued

- In addition to avoiding all the problems from the last chapter (eg caffeine, alarms), here are more tips:

- Keep the same waking and sleeping time each day. Erratic sleep schedules disrupt sleep quality.

- Practice sleep hygiene - lower bedroom temperature, reduce noise, reduce light.

- No alcohol, caffeine, exercise, or long naps before sleep.

- Exercise seems to increase total sleep time and increase the quality of sleep.

- This is more a chronic effect. This does not seem to act immediately on a day-to-day scale - exercise on one day doesn’t necessarily lead to better sleep that night. But worse sleep on one night does lead to worse exercise the following day.

- Eat a normal diet (not severe caloric restriction of below 800 calories per day). Avoid very high carb diets (>70% of calories) since this decreases NREM and increases awakenings.

Sleeping Pills are Bad

- Sleeping pills are typically sedatives that put the body into a state that doesn’t fully resemble sleep (similar to alcohol). The sleep looks different electrophysiologically – the deepest brainwaves are lacking.

- They don’t even really work. Sleeping pills are no better than placebo at reducing the time to fall asleep (even though self-reported satisfaction is higher). The lower quality of sleep causes daytime sleepiness.

- Sleeping pills can kick off a heavily medicated vicious cycle:

- Poor sleep practices or stress reduces sleep.

- Taking sleeping pills causes next-day drowsiness.

- Caffeine use and naps reduce drowsiness, but also reduce the ability to sleep at night, causing more sleeping pill usage.

- Tolerance of sleeping pills causes withdrawal insomnia when stopped, thus maintaining the habit.

- Population studies show that sleeping pills increase mortality in a dose-dependent way. Suggestive causes, possibly with a root cause of abnormal sleep:

- Increased drowsiness in day increase car accidents

- Increased risk of cancer

- Increased infection risk (esp bad for elderly)

- (Shortform note: we can’t rule out that something upstream that disrupts sleeping and thus make people take sleeping pills is also causing all these other disease risks.)

CBT for Insomnia

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a common non-pharmacological method for changing behavior. It’s commonly applied to depression, but there are variants for insomnia.

- CBT has been shown to be more effective than sleeping pills.

- A big part of alleviating insomnia is redeveloping confidence around the ability to sleep. Thus, some practices force insomniacs to restrict their time in bed, maybe even to 6 hours or less. This builds up stronger sleep pressure, and so patients fall asleep faster and regain psychological confidence.

- Other prescriptions:

- Don’t have a clock nearby or you’ll watch the clock and be anxious that you’re not falling asleep.

- If unable to sleep, get out of bed and go back when sleepy. Don’t lie in bed awake

- Go to bed only when you’re sleepy.

- Avoid daytime napping.

- Reduce anxiety-provoking thoughts before bed.

TED Talk Notes

smaller testicles

Brain

sleep after learning as a save button

also need sleep before learning, preparing your brain

without sleep, the brain cannot absorb new knowledge

Two group

sleep group

sleep-depravation group

Learn new things and observe brain activity the next day

Huge difference

Hippocampus

- the informational inbox, receives memory files

- full night sleep, healthy activity in Hippocampus, not visible in those sleep-depraved

- cannot effectively memorize

- big powerful brainwave happened during sleep

- sleep spindles

- deep sleep brain waves act as a file transfer mechinism

- short term to longterm memory

Aging and Dementia

- one feature of aging, your sleep gets worse

- disruption of deep sleep lead to achizmer

- sleeping pills do not help

- instead, inserting small amount of voltage into brain

- amplifying size of brain wave

Daylight saving time

- when we lose one hour, higher heart attack in that day. 24%

- gain one hour, lower heart attack

Sleep lost and immune system

- natural killer cell

- sleep more, get more

- 4 hour sleep lead to a 70% of drop in natural killer cell activity, a concerning state of immune deficiency

- night-shift worker is a actual carcinogen

- the shorter you sleep, the shorter your life

DNA code may even be impaired by a lack of sleep

- change in Gene activity profile

Advice

- Regularity, go to bed and wake up at the same time. everydat

- Keep it cool, core temperature drops 2-3 degress

- 18 degree is the optimal temperature for sleep

Sleep is a biological nessity

- best method yet from mother nature to immortality

- a great public healthy challenge in our time

良好睡前习惯

- 建立一套长期重复的睡前习惯能让身体和大脑产生适应性反应,面部护理,用foam roller放松一下脊椎,在床上读一首博尔赫斯的诗。

- 每天规律入睡和起床:大部分地理位置10点是最理想的睡眠时间,符合日落日出的自然规律。如果无法10点睡也要尽可能在11点前,要保持长期的规律性。

- 建立床的唯一功能性:平时尽量不在床上看电脑和手机,只有休息和睡觉的时候才上床。选用高度适合的枕头,不要过高;床垫软硬适中不要太旧给脊椎提供稳定的支撑。

- 光:睡前保证半小时至一小时不看手机,晚上手机电脑屏幕启用Night Shift尽可能过滤蓝光。同时保证早上日出的自然唤醒。

- 温度:将室内温度稍微调低,睡前洗温水澡甚至冷水澡能更快入眠。

- 气味:考虑香薰机或者无烟香散发淡而安神的味觉分子。

- 睡觉姿势:侧身最理想,也是人类和各种哺乳动物睡觉时下意识选用最多的姿势。

- 心态:不要有压力,不要回想日常事务或者待办事项,不要看时间,尝试Guided Meditation。