Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think

by Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling, Anna Rosling Rönnlund

About the author:

Hans Rosling was a medical doctor, professor of international health and renowned public educator. He was an adviser to the World Health Organization and UNICEF, and co-founded Médecins sans Frontiéres in Sweden and the Gapminder Foundation. His TED talks have been viewed more than 35 million times, and he was listed as one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world. Hans died in 2017, having devoted the last years of his life to writing this book. [[swan song]]

Intro

作者是WTO的医疗专家,大学讲师,多年致力于Making the world a better place. 他从小希望当吞剑马戏表演师,后来发现自己的喉咙构造还真的可以做到。原来吞剑是真的吞下一把钝器,这在很多人看来都是不可能发生的,也包括我。作者用这一行为提醒大家世界也许我们感知中的有很大不一样。所以我们应该永远[[stay hungry stay foolish]]。See also[[语法的底层直觉]]

接着作者问了13个世界相关的问题,关于人口发展,生育,受教育,寿命,贫困比例,疫苗,儿童数量等等的全球性预期。我只回答正确4道题。

大部分受访者得分也都很低。不仅如此,Rosling发现答错有一种往更坏方向预期的倾向(Only actively wrong “knowledge” can make us score so badly.)。这种倾向不仅出现在普通受访者中,高知分子,企业高管,甚至是达沃斯论坛里的UN官员和亿万富翁,在一些常识性预测世界的问题中答错率也都很高。(如果只是随机答错,那么3选1单选题的概率是33.3%,如果答对概率低于33.3%,说明答题者主观上这么认为并答错)

对于这种情况Rosling各种几种解释:

许多人拥有的知识是过时的,离开学校后没有进一步更新,而世界是不断变化的。

就算拥有了最新世界概况的更新,人依然不容易改变。(I shouldn’t have worried. This top international audience who would spend the next few days explaining the world to each other did indeed know more than the general public about poverty. A stunning 61 percent of them got it right. But on the other two questions, about future population growth and the availability of basic primary health care, they still did worse than the chimps. Here were people who had access to all the latest data and to advisers who could continuously update them. Their ignorance could not possibly be down to an outdated worldview. Yet even they were getting the basic facts about the world wrong.)媒体的过度渲染是一个很大原因。

进化过程中大脑的底层认知。参见[[Over-dramatic world-view]]

过度夸张的世界观,是导致我们对于世界认知出现偏差的主要原因。表现为由于过时知识,哗众取宠的媒体渲染,政府宣传,假新闻和错误事实导致的消极化认知世界。但以上原因都只是一部分,我们这种世界观倾向的是由大脑底层认知导致的。

人类进化的节奏没有赶得上技术进化的速度,很多史前有用的生存特指现在成为需要克制的不良欲望。嗜糖就是最大的例子。人类大脑倾向快速做出反应和判断,这样在自然环境下能够迅速对威胁做出反应,提高生存机会,这也是Thinking Fast and Slow里所提到的[[System 1]]。这样的反应方式是有进化优势的,即便在当前远离野外生活的环境下,快速反应[[System 1]]依然有积极意义,减轻大脑负担(If we sifted every input and analyzed every decision rationally, a normal life would be impossible)同时更快速做决策。但如果不加以控制,大脑就会下意识对充满戏剧性,带有爆点的信息印象更深,加上以上提到的媒体,假新闻等的辅助,我们的世界观就会离真实世界越来越远,朝着一个充满偏见的,负面的倾向发展。

通过这本书Rosling希望读者对世界有一个更加清晰正确的认知,厘清真正需要注意的议题。保持心态平和,因为世界本就没有我们所想象的那么充满戏剧性。(This is data as you have never known it: it is data as therapy. It is understanding as a source of mental peace. Because the world is not as dramatic as it seems.)(You will be able to get the world right without learning it by heart. You will make better decisions, stay alert to real dangers and possibilities, and avoid being constantly stressed about the wrong things.)

这种[[Over-dramatic world-view]]和[[System 1]]相似。同时思考的点是在当前[[COVID-19]]肆虐的情况下,以及整个看似疯狂的2020年大背景下,我们是否也只是overreact了呢?

1 The Gap Instinct

从[[1965 vs 2017 Children Mortality Rate]]对比我们能看出如今不同世界之间的gap远没有想象中的那么大,但是许多第一世界的人印象依然停留在几十年前。不仅仅是出生率,其他的统计数据例如受教育程度,民主程度,收入,医疗保险,电力接通率,都和儿童死亡率的改变类似,差距都没有那么明显(The change looks very similar for pretty much any aspect of human lives. Graphs showing levels of income, or tourism, or democracy, or access to education, health care, or electricity would all tell the same story: that the world used to be divided into two but isn’t any longer.)。

75%的人都生活在类似中等收入的国家,不穷不富,都能够通过自己的劳动和努力挣取一份养活自己的工资。Today, most people, 75 percent, live in middle-income countries. Not poor, not rich, but somewhere in the middle and starting to live a reasonable life.

Most people have enough to eat, most people have access to improved water, most children are vaccinated, and most girls finish primary school.

把世界依然看成一个极度分裂的存在是陈旧的观点,是错误的幻想。低收入国家综合情况远比人预估的更好。

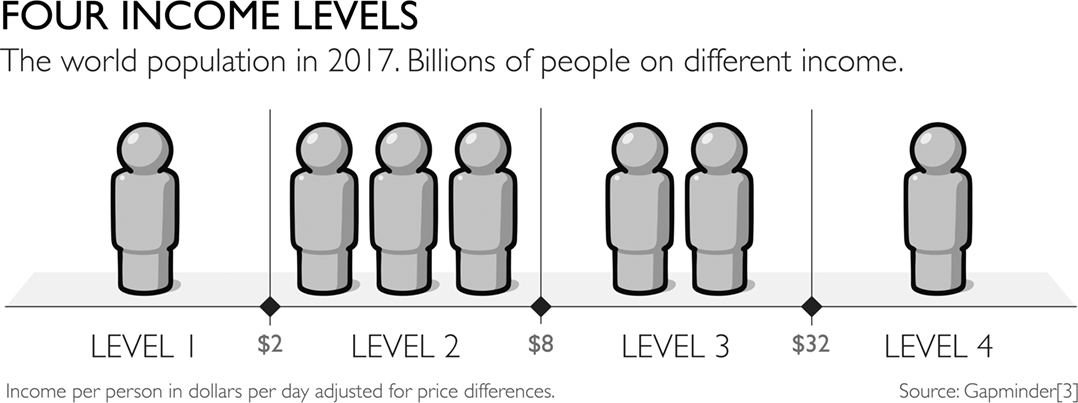

为了更好的给世界国家分类,避免使用发达国家和发展中国家这两个二元化明显的标准。Rosling提出了4分法,从level 1到level 4

- Level 1:

平均每天收入1美元, 交通工具主要靠脚, 每天从远方跳水回家,劈柴取暖, 每餐都只能吃粥。 生病自己无法康复就基本上是死路一条。**极度贫困** 10亿 - Level 2:

日收入4美元 能够骑自行车出行 可以购买食物,包括肉食例如鸡蛋和鸡肉 可以拥有火炉离取水点也更进,孩子们可以去上学而不是去捡柴火 电力不稳定但是有供应 可以睡在买来的垫子而不是泥巴地板上 生病后医疗费用会让你倾其所有,很可能重返Level 1极度贫困 30亿人 - Level 3:

日收入16美元 交通工具升级为摩托车,行动半径变大,可以去更远的镇上工作 直来水和稳定电力 拥有冰箱,每日食物多样化 有积蓄,可以应对医疗费用 孩子们接受教育,有更大的上升可能 偶尔还能小型独度假 20亿人 - Level 4:

日收入$64 you know about this level already. Since you are reading this book, I’m pretty sure you live on Level 4. 当你身处于level 4,你会难以理解前三个level,更难以想象这三个level之间的区别 10亿人

作者花了17年才终于说服世界银行改成了4 level 分类,而UN和其他国际组织还是没有改变(It took the World Bank 17 years and 14 more of my lectures before it finally announced publicly that it was dropping the terms “developing” and “developed” and would from now on divide the world into four income groups. The UN and most other global organizations have still not made this change)。

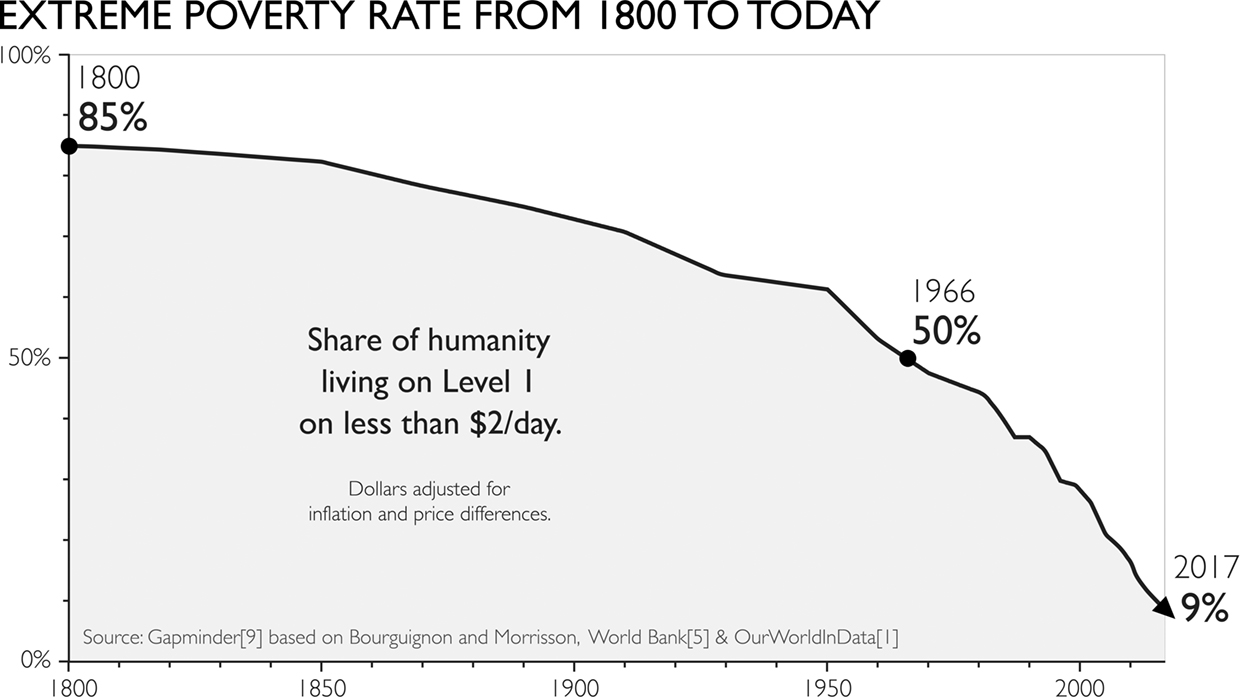

以上是当今的情况,200年前,85%的世界人口都处于level 1, 极端贫困。

The Gap Instinct

Human beings have a strong dramatic instinct toward binary thinking, a basic urge to divide things into two distinct groups, with nothing but an empty gap in between. We love to dichotomize. Good versus bad. Heroes versus villains. My country versus the rest. Dividing the world into two distinct sides is simple and intuitive, and also dramatic because it implies conflict, and we do it without thinking, all the time.

人类有一种把万物一分为二的本能,世界是对立存在的,通过对自然观察人类发现各种对立的元素:白天与黑夜,左与右,英雄与恶人,好与坏,我与你。二分法成为思维底层的一种感知方式。参见[[辩证主义]]”

这也是把世界划分为两类,“一类发达,一类发展中”这样一种思维模式很难消除的原因。且人们往往没有意识到这两类之间的间隔(Gap)是极大的。

How To Control Gap Instinct?

There are three common warning signs that someone might be telling you (or you might be telling yourself) an overdramatic gap story and triggering your gap instinct.”

Beware comparisons of averages.

If you could check the spreads you would probably find they overlap. There is probably no gap at all.

取平均会把群体单一化,两个群体的平均数对比往往造成分裂的假象,用群体分布图往往能有更全面的效果

人们通过这种间隔构造一个过于夸张的世界,更深入观察两个群体之间的个体往往发现没有那么大的差距。Beware comparisons of extremes.

In all groups, of countries or people, there are some at the top and some at the bottom. The difference is sometimes extremely unfair. But even then the majority is usually somewhere in between, right where the gap is supposed to be.

对比极端情况也能产生过于夸张的不真实印象

当你处于level 4, 下面的三个level如果不去了解和亲自体验很难产生直观的区别,这也是为什么level 4的人类更容易二元化分类世界。事实上,level 1, level 2, level 3每一层之间都有极大的差别。以一种平等的视角而非居高临下的姿态才能感知到一个更真实的世界。

2: The Negativity Instinct

负面事物会给我们留下更深刻印象。但别忘记正面信息更难被获取,但他们依然存在,整个世界是积极发展的。

过去一两百年之内整个世界发展显著:

极端贫困率,全世界的极端贫困率急剧下降,1966降至50%,2017年9%

人均寿命

从1800年的31岁到2017年72岁

负面思维的产生原因

Misremembering of the past

忆苦思甜,老人回去过去大多会美化苦难,给人一种过去其实也没多惨的错觉。饥荒,战乱,低人权,其实可以理解成一种自我防御机制,或者是斯德哥尔摩综合征,如果认知上直面一切残忍,很难正常的活下来。类似的例子参考[[房思琪的初恋乐园]]。但如果参考最近看的[[活着]],就能感受到哪怕是50年前的普遍生活是有多么苦。

这种潜意识美化让我们没有意识到当代生活和从前对比之间的巨大差距。Selective reporting

永远是战乱饥荒疾病政治动荡恐怖袭击大幅裁员经济萧条最吸引人眼球,也最容易登上头条。逐渐改善的进步没有任何爆点。但不代表不存在。

媒体自由和技术进步让我们能不出门知千里事,这是人类的进步,但报道消息的普遍负面化加深了世界在变差的感观。And thanks to increasing press freedom and improving technology, we hear more, about more disasters, than ever before. When Europeans slaughtered indigenous peoples across America a few centuries ago, it didn’t make the news back in the old world. When central planning resulted in mass famine in rural China, millions starved to death while the youngsters in Europe waving communist red flags knew nothing about it. When in the past whole species or ecosystems were destroyed, no one realized or even cared. Alongside all the other improvements, our surveillance of suffering has improved tremendously. This improved reporting is itself a sign of human progress, but it creates the impression of the exact opposite.Feeling, not thinking

人们常说世界变得越来越疯狂,说这句话的时候没有思考,完全凭感觉。What are people really thinking when they say the world is getting worse? My guess is they are not thinking. They are feeling.

"I agree. Everything is not fine. We should still be very concerned. As long as there are plane crashes, preventable child deaths, endangered species, climate change deniers, male chauvinists, crazy dictators, toxic waste, journalists in prison, and girls not getting an education because of their gender, as long as any such terrible things exist, we cannot relax."

如何控制负面思维

Bad and better”

Think of the world as a premature baby in an incubator. The baby’s health status is extremely bad and her breathing, heart rate, and other important signs are tracked constantly so that changes for better or worse can quickly be seen. After a week, she is getting a lot better. On all the main measures, she is improving, but she still has to stay in the incubator because her health is still critical. Does it make sense to say that the infant’s situation is improving? Yes. Absolutely. Does it make sense to say it is bad? Yes, absolutely. Does saying “things are improving” imply that everything is fine, and we should all relax and not worry? No, not at all. Is it helpful to have to choose between bad and improving? Definitely not. It’s both. It’s both bad and better. Better, and bad, at the same time. 以过去一百年为基准的看世界,100年前的世界就像是一个早产的婴儿,各种问题,但虽然起点低,各方面却都在不断好处。世界很多地方也许依然不行,但要意识到实在不断进步的。

正确认知负面新闻

Remember that the media and activists rely on drama to grab your attention. Remember that negative stories are more dramatic than neutral or positive ones. Remember how simple it is to construct a story of crisis from a temporary dip pulled out of its context of a long-term improvement. Remember that we live in a connected and transparent world where reporting about suffering is better than it has ever been before.负面新闻比正面新闻传播的更广。统计数据是更加直观的正面新闻来源。”

这里的假设是一个社会是缓慢的不断向前的进步,所以才能认为正面新闻也是越来越多。如果生活在叙利亚或者朝鲜还持这种乐观态度是不现实的。首先得承认自己所在社会制度的正当性,然后才能采取更积极认知。可能这就是中文媒体里所说的“传递正能量吧”。

3: The Straight Line Instinct

Factfulness is … recognizing the assumption that a line will just continue straight, and remembering that such lines are rare in reality.

To control the straight line instinct, remember that curves come in different shapes.

Don’t assume straight lines. Many trends do not follow straight lines but are S-bends, slides, humps, or doubling lines. No child ever kept up the rate of growth it achieved in its first six months, and no parents would expect it to.

人有假定一条线的延伸趋势为直的倾向。源自自然界中物体运动的趋势,滚动的物体,飞来的石头(稍微受重力下降)。这样的一种捷径思维帮助人类更好预测周围环境的动态。提高生存几率。这种直觉如今依然有用,比如开车的时候根据周围车的轨迹预测接下来的行进路线。#[[进化论]]

但每一种捷径直觉都有缺点。人类的线性直觉在预测一些事先不了解的倾向时会产生错误。

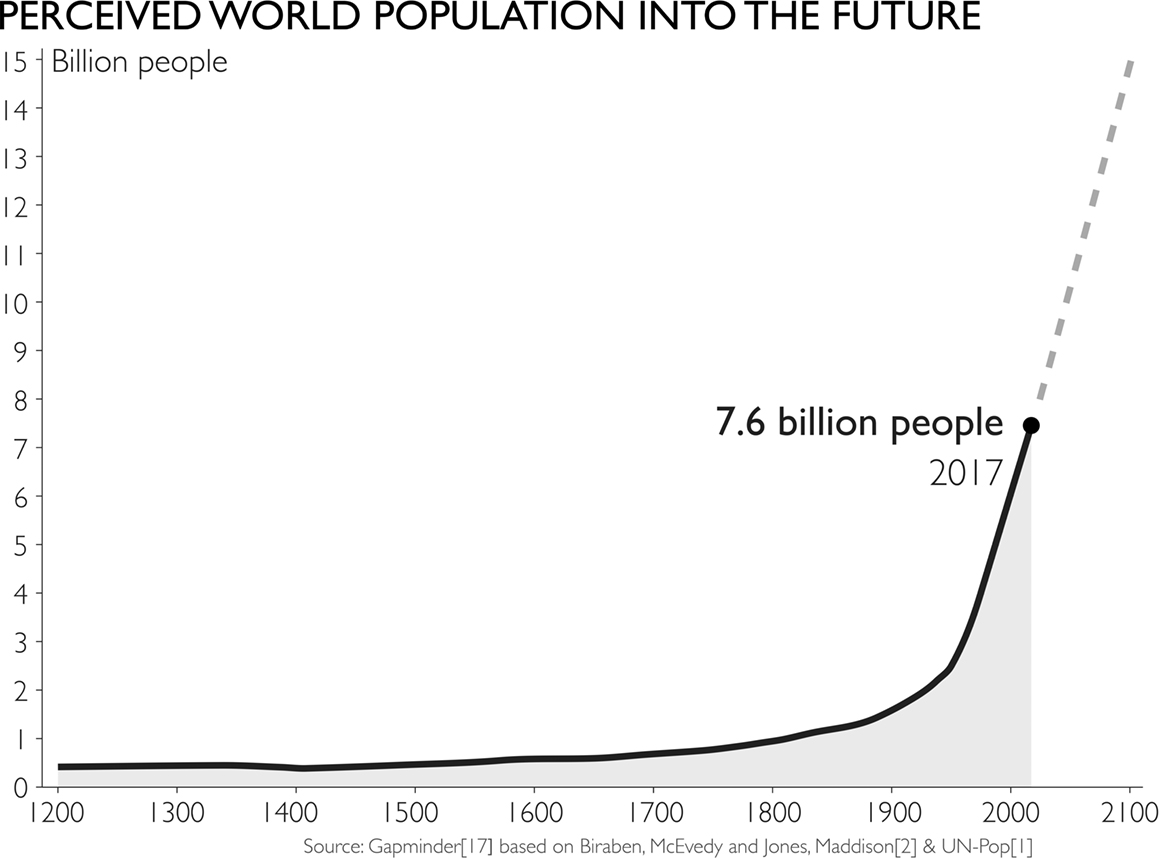

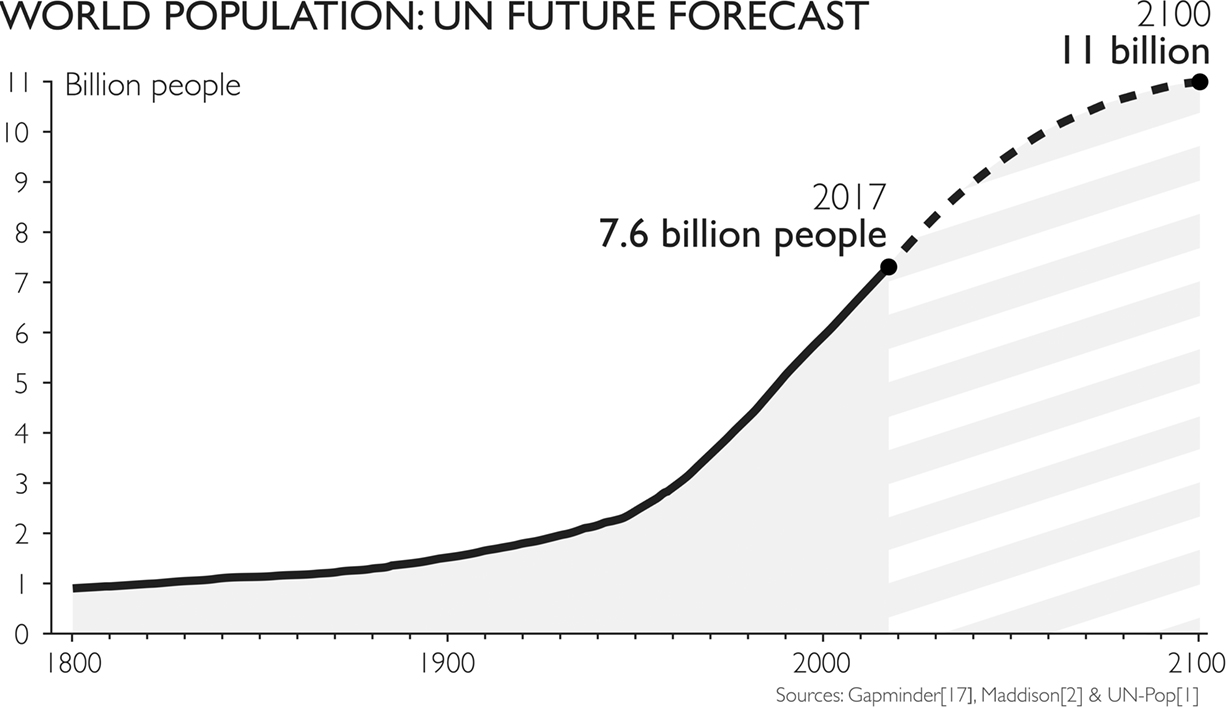

人口增长趋势

从上图看出过去几十年人口数量迅速增长,这是由于技术进步,生产力提升,人类生存环境普遍变好。如果按照直线直觉的惯性那么接下来人口增长爆炸,但UN专家(对该问题进行研究和调查)给出的预测如下图:

这张图把横坐标延长放大,没有和过去几百年对比整个趋势看起来缓和很多。其实是一种[[坐标轴刻度陷阱]]。

但总体上的趋势不是一条直线,而是上升趋平。

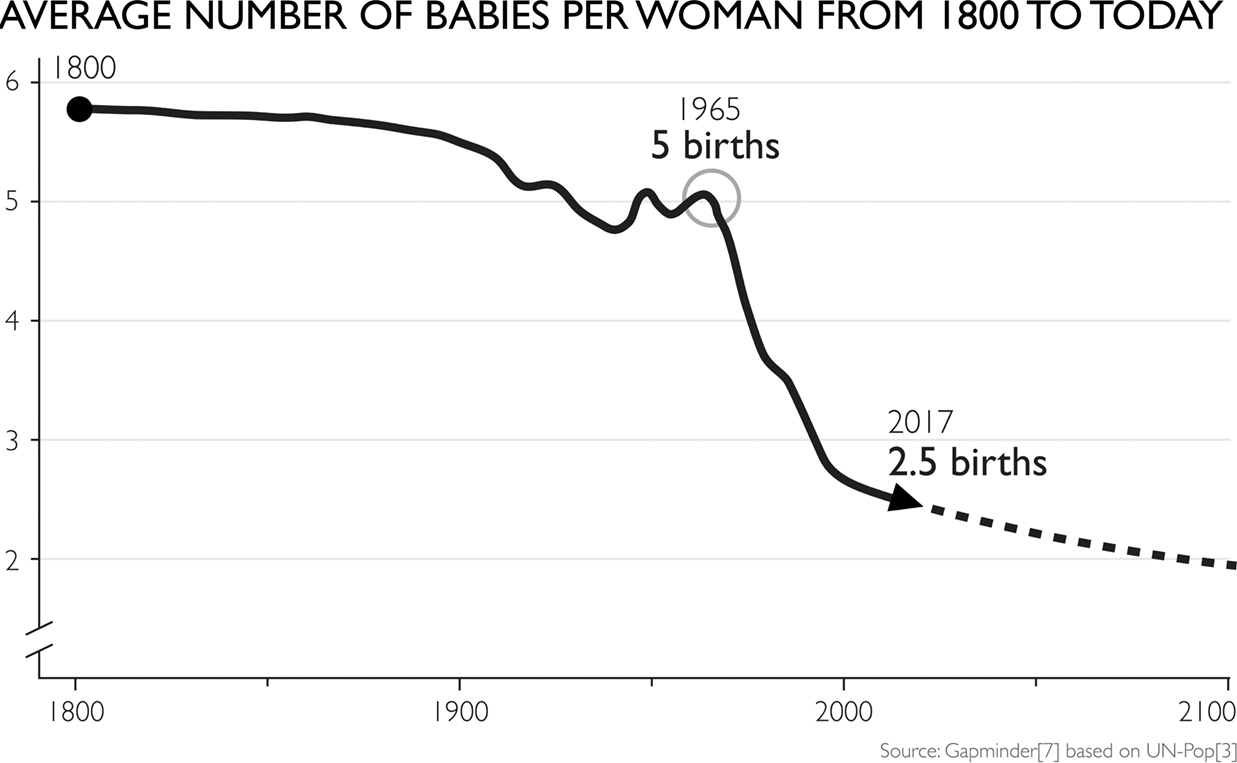

极端贫困总是和高生育率挂钩,人们担心地球人口爆炸增长,认为穷人生孩子太多。甚至有人反对帮助脱贫,因为贫困人口生育死亡率高,如果都活了会造成人口更大负担。但这是一个逻辑谬误。因为人一旦脱贫,接受了更好的教育,尤其是对女性进行更好的教育,提供更好的医疗条件和避孕措施,人们更加优化的方式是少生孩子,提供优质养育。多生是对抗穷困的风险对冲,因为死亡率高,因为能有更多劳动力。一旦脱贫则生育率迅速降低。这也是我们观察到的主流趋势。

Real Balance in mankind history

For thousands of years up to 1800 the population curve was almost flat. Have you heard people say that humans used to live in balance with nature?

Well, yes, there was a balance. But let’s avoid the rose-tinted glasses. Until 1800, women gave birth to six children on average. So the population should have increased with each generation. Instead, it stayed more or less stable. Remember the child skeletons in the graveyards of the past? ^^On average four out of six children died before becoming parents themselves, leaving just two surviving children to parent the next generation^^. There was a balance. ^^It wasn’t because humans lived in balance with nature. Humans died in balance with nature.^^ It was utterly brutal and tragic.

Today, humanity is once again reaching a balance. The number of parents is no longer increasing. But this balance is dramatically different from the old balance. The new balance is nice: the typical parents have two children, and neither of them dies. ^^For the first time in human history, we live in balance^^.

How To Control the Straight Line Instinct or Not All Lines Are Straight

避免直线思维最好的方式就是多储备几种数据统计模型:

Straight Lines 线性趋势

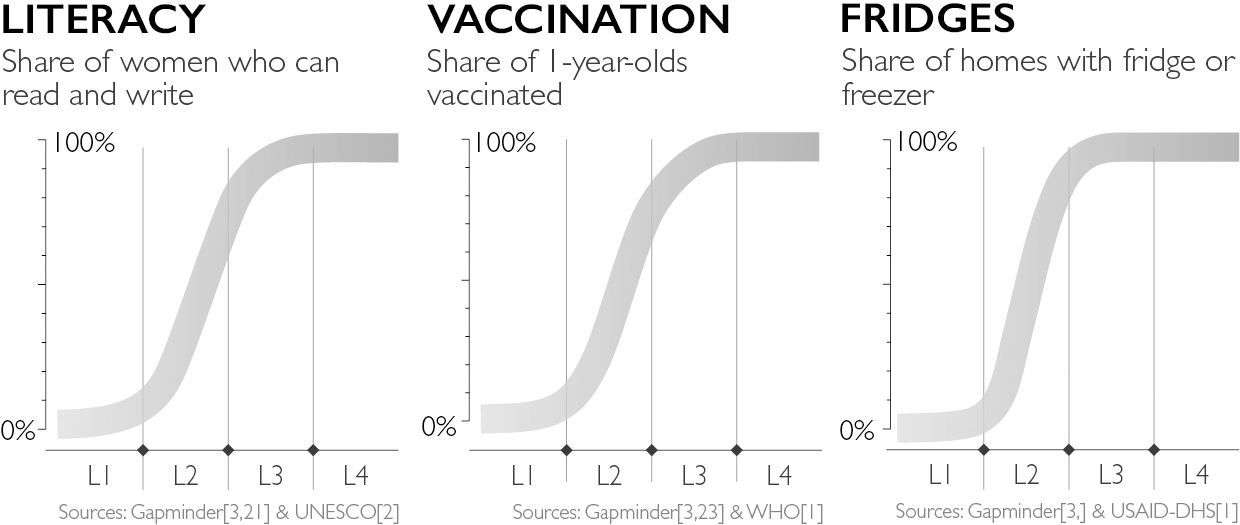

确实还是有一些线性的关系存在,但远没有想象中的多。S-Bends S型趋势

S型趋势,前期平缓,中期迅速上升,后期平缓

例如人均收入和识字率,和疫苗接种率,和冰箱拥有率

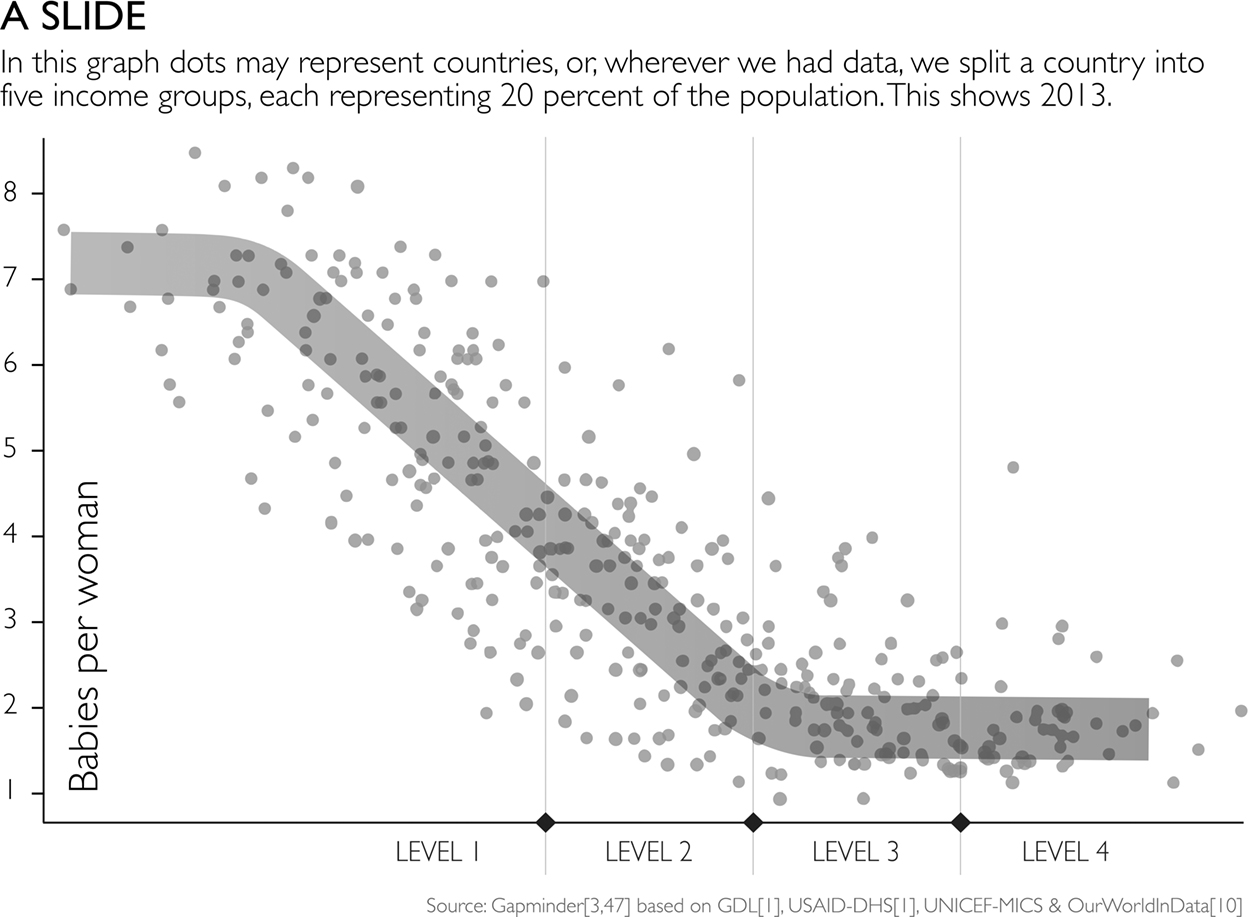

Slides 滑梯曲线

收入水平和生育率

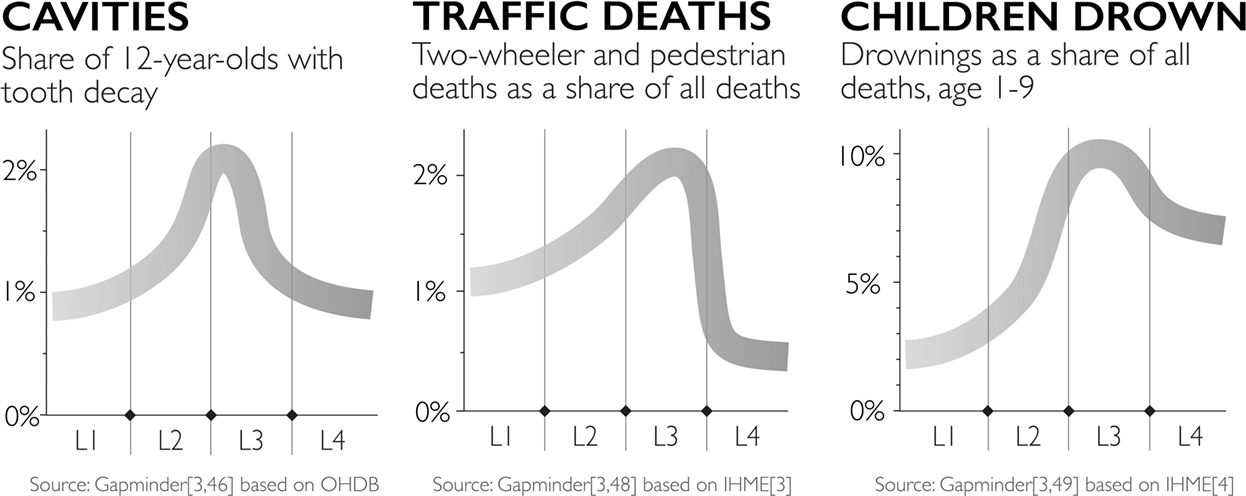

Humps 驼峰型曲线

口腔卫生,极度贫困没糖吃,收入增长有糖吃,但医疗保险和健康饮食意识没跟上,反而龋齿率增高,等收入继续上升,再下降。

类似还有交通事故和儿童溺水率。

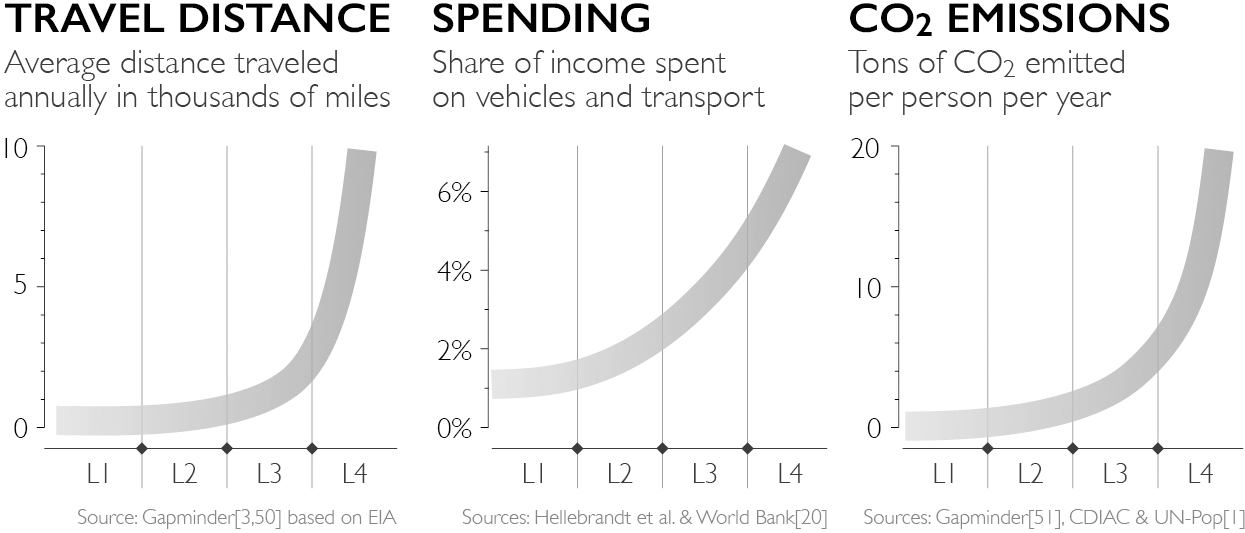

倍增型曲线

呈指数形式增长,例如细菌的繁殖,棋盘里的麦子数量,病毒的传染率。其他的还有人类出行距离,花销和二氧化碳排放量,随着收入的增长。

4: The Fear Instinct

Recognizing when frightening things get our attention, and remembering that these are not necessarily the most risky. Our natural fears of violence, captivity, and contamination make us systematically overestimate these risks.

To control the fear instinct, calculate the risks.

恐惧的本能让我们丧失理性思考的能力。When we are afraid, we do not see clearly. Critical thinking is always difficult, but it’s almost impossible when we are scared. There’s no room for facts when our minds are occupied by fear.

十种夸大直觉的资讯更容易抓住我们眼球,使我们忽略了更重要,更真实的信息。Most information doesn’t get through, but the holes do allow through information that appeals to our dramatic instincts. So we end up paying attention to information that fits our dramatic instincts, and ignoring information that does not.

我们必须时刻小心谨慎,才不至于将小概率事件认作普遍性规律,才能看到更真实的世界。If we are not extremely careful, we come to believe that the unusual is usual: that this is what the world looks like.

在这些夸大的直觉中,恐惧是最容易影响我们接受信息方式的。Of all our dramatic instincts, it seems to be the fear instinct that most strongly influences what information gets selected by news producers and presented to us consumers. 媒体会选择性的报道那些最能够吸引眼球的新闻,而那些通常是调动了我们的恐惧直觉。[[007]]择日而亡里的新闻大亨Elliot Carver经典台词:There is no news than bad news.

人类最普遍且共有的一些恐惧:蛇,蜘蛛,高度,被困在狭小空间内,公共演讲,针刺,坐飞机,老鼠,陌生人,狗,人群,鲜血,黑暗,火,溺水,等等。When people are asked in polls what they are most afraid of, four answers always tend to turn up near the top: snakes, spiders, heights, and being trapped in small spaces. Then comes a long list with no surprises: public speaking, needles, airplanes, mice, strangers, dogs, crowds, blood, darkness, fire, drowning, and so on.

这一系列恐惧根植于大脑,源自最古老的人类进化。野外求生的祖先只有对肢体伤害,囚禁,有毒食物格外警惕才能获得更大的生存优势。#[[进化论]] These fears are hardwired deep in our brains for obvious evolutionary reasons. Fears of physical harm, captivity, and poison once helped our ancestors survive. 综合起来就是人们对死亡的恐惧和对繁衍的渴望(也许人类作为一个种群并没有那么害怕死亡,更害怕的是无法繁衍,这里就涉及到非个体,种群的混沌意志),可以进一步分类

- Physical Harm 身体伤害

- Violence caused by people, animals sharp objects or forces of natures.

- Contamination: by invisible substances that can infect or poison us.

- Fear of height: 靠悬崖太近且毫不畏惧的人摔死了不少

- 蛇,蜘蛛,老鼠,狗都带来肉身伤害,咬或者毒

- 黑暗:无法看见,不确定性,可能会摔倒受伤,可能会被动物袭击

- 针刺,火,鲜血,溺水都联想到疼痛和死亡

- 陌生人,人群则是地方不信任没见过的他人的攻击

- 公共演讲算是一种social anxiety,害怕尴尬和被拒绝(因此降低潜在交配几率?…),另说。

- Captivity: entrapment, loss of control or freedom.

时至今日,恐惧本能在Level 1和Level 2贫困人群之间有更加实用的价值,因为这里的人群可能扔需要面对来自自然的各种威胁。These fears are still constructive for people on Levels 1 and 2. For example, it is practical, on Levels 1 and 2, to be afraid of snakes. Sixty thousand people are killed by snakes every year. Better to jump one too many times when you see a stick. Whatever you do, don’t get bitten. There’s no hospital nearby and if there is you can’t afford it.

Rosling的学生问一为贫困地区条件极为落后的助产妇她最想要的一件工具是什么,助产妇回答:手电筒,这样夜间她在村与村之间行进的时候就可以看得清楚路,不怕被蛇咬。

对于Level3、4的人群来说,原始恐惧本能更多的时候起到副作用(但我们也不能因此说完全就不需要这些本能了,因为谁能保证自己能永远出在极度文明的地区呢?)。On Levels 3 and 4, where life is less physically demanding and people can afford to protect themselves against nature, these biological memories probably cause more harm than good.

高收入国家,人们每日接触到的各类讯息,绑架,飞机失事,地震,各种自然灾害。而相比之下有很多致死率更高或者更严重的问题因为是长期缓慢的发生并没有吸引媒体的关注,从而也无法被广为人知。In fact the biggest stories are often those that trigger more than one type of fear. Kidnappings and plane crashes, for example, each combine the fear of harm and the fear of captivity. Earthquake victims trapped under collapsed buildings are both hurt and trapped, and get more attention than regular earthquake victims. The drama is so much stronger when multiple fears are triggered.

以下是集中媒体常常报道的事件,这些事件确实耸人听闻,但根据死亡人数来看其危害性被媒体传播高估和放大了。

- 自然灾害

新闻中永远都是地震,山火,海啸,洪涝等自然灾害。但因为自然灾害而死亡的人数再过去几十年之间已经大大降低。尤其是在level 3、4区间。主要原因并不是地球变得更温柔,而是更多的国家脱贫,有了更加充分的财政预算和高科技用以应对甚至是预测各类自然灾害。The reason natural disasters kill so many fewer people today is not that nature has changed. It is that the majority of people no longer live on Level 1. Disasters hit countries on all income levels, but the harm done is very different. With more money comes better preparedness. The graph below shows the average number of deaths from natural disasters per million people over the last 25 years, on each income level.

但此类自然灾害依然是人内心深处的一种恐惧,也是媒体放大性报道的原因之一。

但有一点需要注意的是:

尽管长期来看的趋势是不断好转的,但遇到当下正在发生的灾害,当我们看到那些正在受苦的同类时,所有的预测和表格都不再重要。应该尽到自己力所能及的义务去帮助他们,心生怜悯。趋势固然重要,但对个体的关注才是我们作为人类的最大优势之一。所谓人性之所在。

在危机过后,别忘了大的趋势,冷静下来,将资源运用到最需要预防的领域。不能让恐惧影响决策。

这里的一个问题就是政府做决策思考预算拨给哪些应急部门是一个综合考量过程,死亡人数只是一个因素,政府还会考虑政治影响,媒体关注度和民意。综合下来也许并不会做出纯粹最符合死亡统计的决策。

9000人死于尼泊尔2015年地震,全世界目光集聚于此,但与此同时十天内全世界也有9000个孩子死于饮水污染导致的腹泻,但没有多少媒体关注。

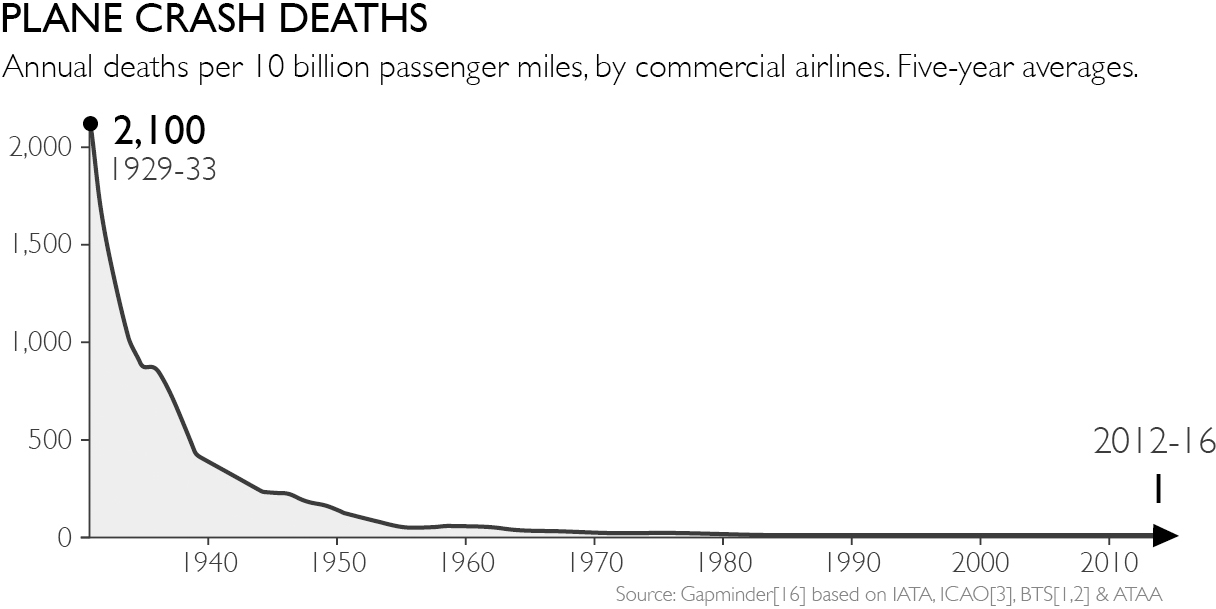

空难

初期空难率很高,1930年代。而现在,例如2016年,全球4000亿次航班,十次致命事故,致死率0.0025%。但没有媒体会去报道航班有多安全,因为没有新闻价值。

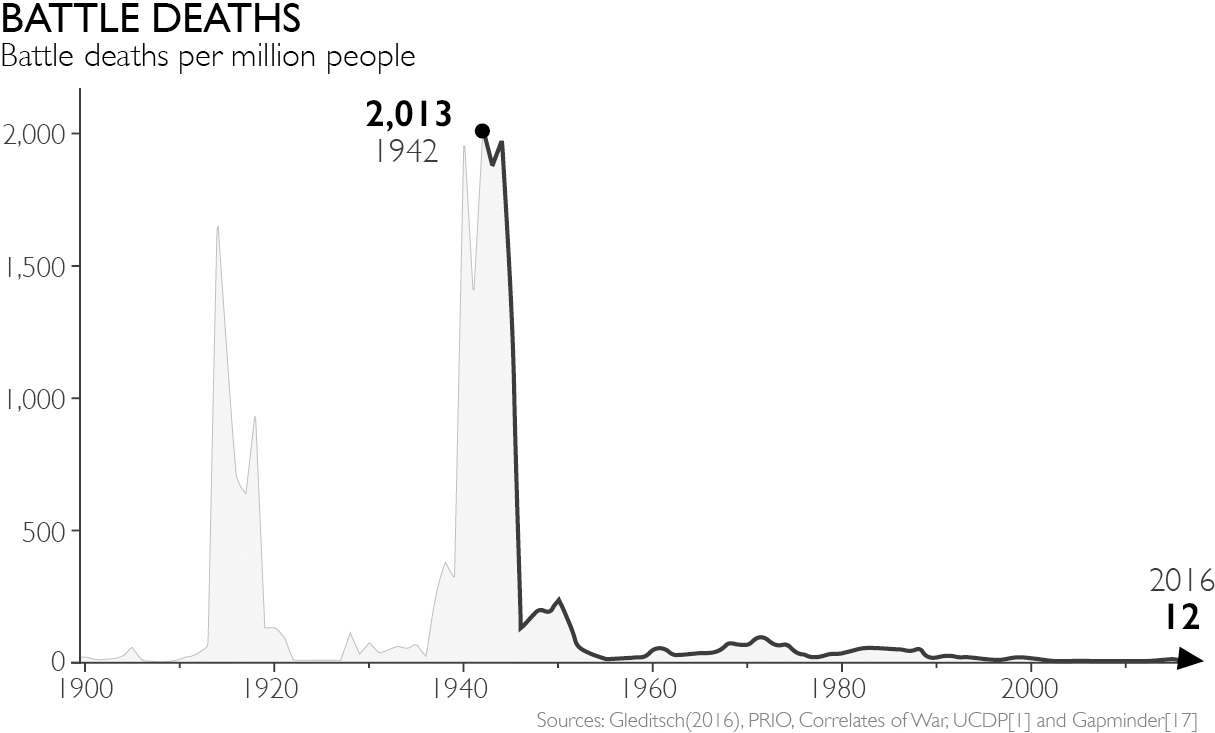

战难

人类处与有史以来最和平的年代。

但叙利亚的战事依然是全时间媒体的焦点,这是媒体天然的报道逻辑,也无可指摘。各类污染

核泄漏污染,切尔诺贝利,福岛地震

上世纪各种没有被监管的化学制剂,比如杀虫剂DDT,比如杜邦公司的化学制剂,给人身体造成各种长期损伤。

留下了后遗症,chemophobia,化学恐惧症。导致儿童疫苗接种,核电站依然被许多人反对。这种反对始于逻辑思考,也终于逻辑思考,恐惧蒙蔽了部分人群接受真实统计数据的能力和意愿。

As a side effect, we have been left with a level of public fear of chemical contamination that almost resembles paranoia. It is called chemophobia.

This means that a fact-based understanding of topics like childhood vaccinations, nuclear power, and DDT is still extremely difficult today. The memory of insufficient regulation has created automatic mistrust and fear, which blocks the ability to hear data-driven arguments.

不谈剂量说毒性的都是耍流氓!Chemophobia also means that every six months there is a “new scientific finding” about a synthetic chemical found in regular food in very low quantities that, ^^if you ate a cargo ship or two of it every day for three years, could kill you.^^ At this point, highly educated people put on their worried faces and discuss it over a glass of red wine. The zero-death toll seems to be of no interest in these discussions. The level of fear seems entirely driven by the “chemical” nature of the invisible substance.恐怖主义

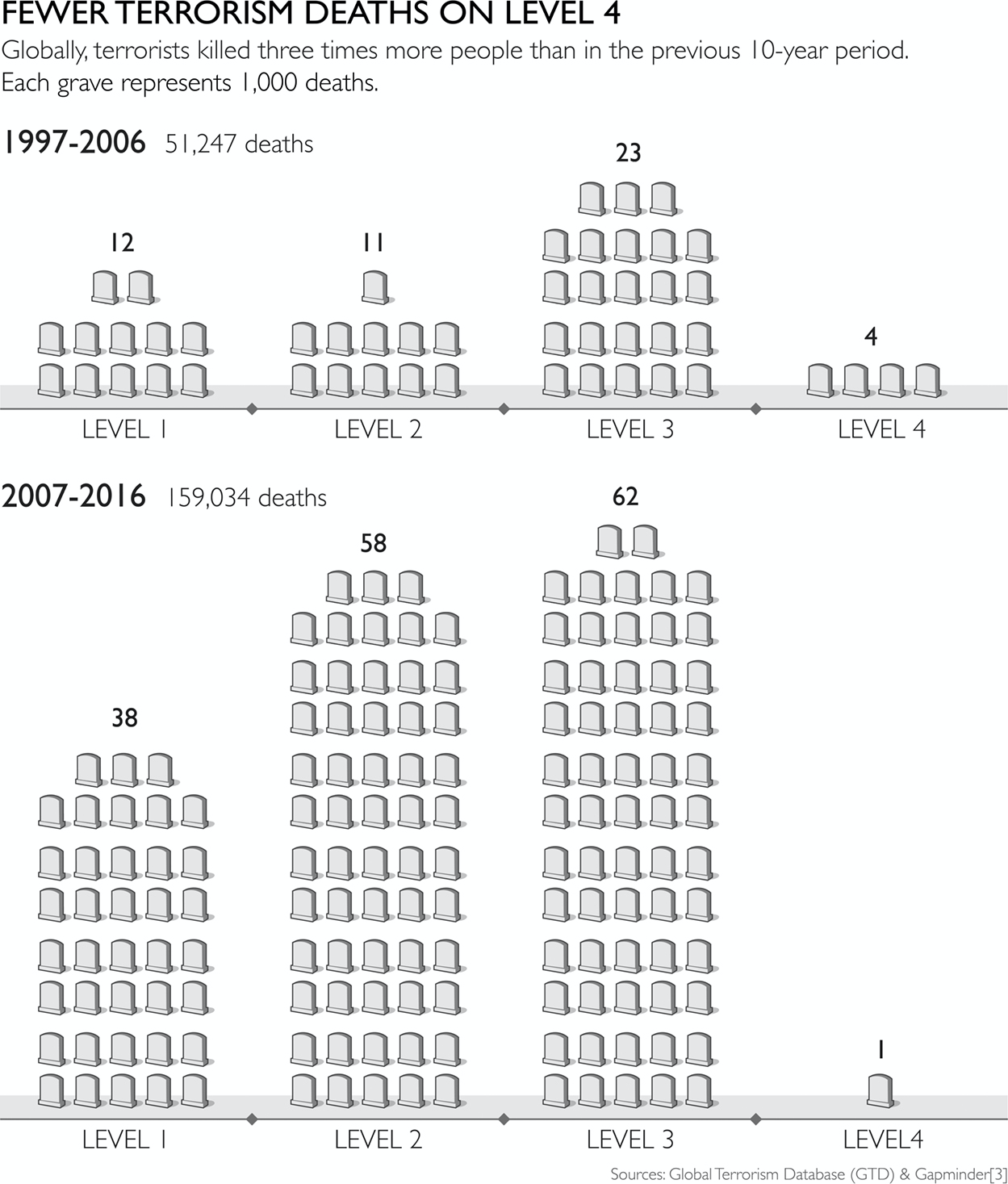

恐怖主义在过去十年内有抬头趋势。恐怖分子比媒体更善于操控人类恐惧直觉。If there’s one group of people who have fully understood the power of the fear instinct, it’s not journalists. It’s terrorists.

恐怖主义在发达国家致死人数越来越少,当前主要集中在Level 3。

在美国过去20年里,恐怖主义平均致死159人,911占大比重。而与酒精相关的死亡人数是平均每年69,000人。单纯概率上来讲,美国人50倍更可能因为酒精相关的事故死亡。但发达国家的新闻聚焦永远是在恐怖主义上,因为它传播了更多的恐惧。

we prioritize our fear to something based on mainly media coverage

让人恐惧的事物和危险的事物是两种不同的存在。一件事物的让人恐惧程度取决于其危险程度媒体曝光度。理性分辨区别帮助我们做出更好决策。不要让原始的进化本能驱动你的行为。Because “frightening” and “dangerous” are two different things. Something frightening poses a perceived risk. Something dangerous poses a real risk. Paying too much attention to what is frightening rather than what is dangerous—that is, paying too much attention to fear—creates a tragic drainage of energy in the wrong directions.

I would like my fear to be focused on the mega dangers of today, and not the dangers from our evolutionary past.

To control the fear instinct, calculate the risks.

- The scary world: fear vs. reality. The world seems scarier than it is because what you hear about it has been selected—by your own attention filter or by the media—precisely because it is scary.

- Risk = danger × exposure. The risk something poses to you depends not on how scared it makes you feel, but on a combination of two things. How dangerous is it? And how much are you exposed to it?

- Get calm before you carry on. When you are afraid, you see the world differently. Make as few decisions as possible until the panic has subsided.

5: The Size Instinct

孤立数据没有意义,看起来很大或者很小,但只有和其他数据做对比才能反映真实情况。

如何避免规模直觉?

A lonely number always makes me suspicious^^ that I will misinterpret it. A number that I have compared and divided can instead fill me with hope.

对比,Compare

要了解数据真正的意义,必须进行对比。可以是时间上的,可以是空间上的。比如:

孤立数据2016年420万婴儿死亡,触目惊心的数据。对比1960年1440万婴儿死亡。还是能看出来婴儿死亡率逐步下降。

各种瘟疫的死亡人数,单看几十万人,几百万人都很可怕,但只有对比才能知道最严重的是[[西班牙流感]]占总体比例,Divide

光看孩子的死亡人数还不够,还有获取孩子的总出生人数,如果分母有变化,那么死亡率也有不同。When you see one number falling it is sometimes actually because some other background number is falling. To check, we need to divide the total number of child deaths by the total number of births.Per Capita 人均也很重要。

二氧化碳排放量欧美国家只对比总排放量,然后得出中国印度大有超过美国的结论。但应该考虑到国家人口,一旦人均化对比,欧美国家排放量远超中印。”

6. The Generalization Instinct

通过个体特点来总结归纳总群特点是本能,这样才能更好的预测周边环境。也是一种生存本能。#[[进化论]] 即便现在依然有用。但如果放任这种直觉会做出错误判断。

非洲是地理跨度极大,但我们下意识把非洲人作为一个统称。但非洲不同国家都有不同的文化和经济水平。笼统的说这是一个“非洲问题”,是无知的表现。同时也许这种错误的认知会错失投资机会。Africa is a huge continent of 54 countries and 1 billion people. In Africa we find people living at every level of development: in the bubble chart above I have highlighted all the African countries. Look at Somalia, Ghana, and Tunisia. It makes no sense to talk about “African countries” and “Africa’s problems” and yet people do, all the time. It leads to ridiculous outcomes like Ebola in Liberia and Sierra Leone affecting tourism in Kenya, a 100-hour drive across the continent. That is farther than London to Tehran.

If someone offers you a single example and wants to draw conclusions about a group, ask for more examples. Or flip it over: i.e., ask whether an opposite example would make you draw the opposite conclusion. If you are happy to conclude that all chemicals are unsafe on the basis of one unsafe chemical, would you be prepared to conclude that all chemicals are safe on the basis of one safe chemical? 以偏概全的时候反过来思考一下,如果检查出化学物质有毒能够得出所有化学品都不安全,进而演化出对疫苗的抵制。那么反过来检查出另一种化学制剂完全无毒甚至有益身体健康是否能得出所有化学品都是安全的?

人们对纯天然似乎也有一种进化上的喜爱。如果两个番茄在分子层面所有的构成都一模一样,营养一模一样,外表也一模一样,价格也一模一样,大部分人还是会倾向选择天然番茄。

为了克制这种以偏概全的直觉,我们应该

- Look for differences within groups. Especially when the groups are large, look for ways to split them into smaller, more precise categories.”

- Look for similarities across groups.

- Beware of “the majority.”

严格意义上来讲,超过50%就可以用majority形容。然而51%和99%差别巨大,所有看到他人使用这个概念,为了更明确理解,应该询问具体百分比。 - Beware of vivid examples. Vivid images are easier to recall but they might be the exception rather than the rule.”

- Assume people are not idiots. When something looks strange, be curious and humble, and think, In what way is this a smart solution?”

7. The Destiny Instinct

许多看起来毫无改变的事物(国家,宗教,个人)其实一直都在缓慢改变,只是观感上不明显。看上去是一动不动的石头,其实是缓慢移动的乌龟。滴水穿石,渐进的,小的不断进步也会逐渐累积成为大改变,我们需要承认改变的可能性,摒弃认为一切都是内定,不可能改变的命中注定思维。The destiny instinct is the idea that innate characteristics determine the destinies of people, countries, religions, or cultures. It’s the idea that things are as they are for ineluctable, inescapable reasons: they have always been this way and will never change. This instinct makes us believe that our false generalizations from [[Generalization Instinct 以偏概全 ]], or the tempting gaps from [[The Gap Instinct]], are not only true, but fated: unchanging and unchangeable.

[[进化论]] 认识上来看,人们此前生存的环境一直趋于稳定,一旦安顿下来后注意力不再放在时刻评估目前环境是否安全上,这种内定的稳定性假设使得精力能被更多分配给其他行为。It is easy to see how this instinct would have served an evolutionary purpose. Historically, humans lived in surroundings that didn’t change much. Learning how things worked and then assuming they would continue to work that way rather than constantly reevaluating was probably an excellent survival strategy.”

宣称自己所属族群有某个特定命运是一种很好用的做法,有助让大家团结于一个大概永不改变的目标,还激发对其他群族的优越感。这对部落、国家和帝国取得力量十分重要。It’s also easy to understand how claiming a particular destiny for your group can come in useful in uniting that group around a supposedly never-changing purpose, and perhaps creating a sense of superiority over other groups. Such ideas must have been important for powering tribes, chiefdoms, nations, and empires.

但是如今然而现在宿命型直觉会让我们没有妥善更新知识,看不见周遭社会的巨大变革。But today, this instinct to see things as unchanging, this instinct not to update our knowledge, blinds us to the revolutionary transformations in societies happening all around us.”

社会与文化不是石头一块,不会改变也无从改变。社会与文化是会动的。西方社会与文化会动,非西方社会与文化也会动──通常动得远远更快。只是除了网路、智慧型手机与社群媒体等最快速的文化转变之外,其他变动往往不够快,所以未获注意或报导。这也是因为[[Negativity Instinct 负面直觉]]导致的选择性报道。Societies and cultures are not like rocks, unchanging and unchangeable. They move. Western societies and cultures move, and non-Western societies and cultures move—often much faster. It’s just that all but the fastest cultural changes—the spread of the internet, smartphones, and social media, for example—tend to happen just a bit too slowly to be noticeable or newsworthy.”

认为非洲永远赶不上欧洲。认为“伊斯兰世界”与“基督教世界”有根深柢固的差异。出于宿命型直觉,我们可能认为某个大洲、宗教、文化或国家将会(或必定)永不改变,原因出在他们抱持不变的传统“价值观”:这类说法一而再出现,如新瓶换旧酒。乍看似有分析依据,细究却往往是出于直觉的偏误。这类高傲说法经常只是出于让感觉掩盖事实。

两百年前清朝也是这么想的,其他蛮夷之国怎会赶得上我天朝上国。

Cultures, nations, religions, and people are not rocks. They are in constant transformation.Thirty-five years ago, India was where Mozambique is today. It is fully possible that within 30years Mozambique will transform itself, as India has done, into a country on Level 2 and a reliable trade partner. ^^Mozambique has a long, beautiful coast on the Indian Ocean, the future center of global trade. Why should it not prosper?

The destiny instinct makes it difficult for us to accept that Africa can catch up with the West. Africa’s progress, if it is noticed at all, is seen as an improbable stroke of good fortune, a temporary break from its impoverished and war-torn destiny. 宿命性直觉也会让我们对目前发生的变化不以为然,以为西方各国经济的减速只是短暂的休整,不就就会重新提速。

The same destiny instinct also seems to make us take continuing Western progress for granted, with the West’s current economic stagnation portrayed as a temporary accident from which it will soon recover. 宿命感由多方面因素导致,对未来预期不能只看非洲的海岸线有多么美丽资源有多么发达,bad political structure makes the future more unpredicatable. Many unexpeceted factors can turned a country upside down. 就像A Gentleman in Moscow所提到的

But under certain circumstances, the Count finally acknowledged, this process can occur in the comparative blink of an eye. Popular upheaval, political turmoil, industrial progress—any combination of these can cause the evolution of a society to leapfrog generations, sweeping aside aspects of the past that might otherwise have lingered for decades. “

根据已有信息的预测也会产生宿命感,你可以说这是宿命感,也可以说这是更务实的做法。西方世界对自己有信心也基于此,整体稳定,抗压强。

很多结论把宗教和生育率挂钩,大男子主义和种族挂钩,最后发现这些都是和经济水平相关性最强。GDP上来后不管是什么宗教什么种族,生育率都下去了,男女平等概念也愈发普及。

(但穆斯林生育率高和穆斯林贫穷这两个到底谁是因谁是果就难说了。)

如何控制?

- 缓慢变化也是变化

- 时刻更新个人认知

- 一年跨度也许不够,和上个年龄段的人多聊聊,感受一下变化。

- 收集文化改变的例子

8. Single Perspective Instinct

单一视角看待问题制约想象力,从多个角度观察思考

为了扭转单一观点直觉偏误,你要有整个工具箱而非一把槌子。懂得察觉单一观点可能局限自已的想像,然后想到不妨试着从许多角度来看问题,方能获得更准确的了解,提出更实际的解方。

- 检验你的想法:别只看支持自身观点的正面佐证,而是请不同意你的人检验你的想法,并找出他们的漏洞。

- 专业有局限:别对专业以外的领域捞过界:对不懂的事物要虚心。此外,别人的专业也有局限,你同样得小心留意。

- 槌子与钉子:如果你擅长使用某个工具,你会太常想去用它。如果你深入了解了某个问题,你容易夸大那个问题或解方的重要性。切记,没有哪个工具处处适用。如果你最爱的点子是槌子,记得找其他有螺丝起子、扳手和卷尺的同事,对其他领域的想法抱持开放态度。

- 看数据,但别“只”看数据:不靠数字不能了解世界,单靠数字同样不能。要看到数字背后的现实世界。

- 当心简单的想法与解法:历史上不乏许多空想家,凭一个乌托邦愿景替恐怖恶行辩护。你要欢迎复杂的思考,对照不同的想法,寻求折衷,视情况决定怎样解决问题。

9. Blame Instinct

怪罪型直觉是替某件坏事找出一个简单清楚的元凶。

在出状况的时候,我们似乎很自然会认为是某个可恶鬼故意为之。我们爱认为坏事必有因,是某个有权有势的恶人在搞鬼:否则世界会无从预料,令人困惑与胆寒。

出于怪罪型直觉,我们往往夸大特定个人或群体的重要性,无法妥善依事实理解世界:我们满心想找出祸首,一旦自认找出就只想揍那人一拳,不再设法在别处找解释。出于怪罪型直觉,我们沉溺在过于简单的指控,没看见更复杂的真相,没留意对的地方,也就很难解决问题,防止坏事重演。

好事同样会触发这个直觉。“称许”和“怪罪”一样容易。当好事发生,我们会很快归功于某个人或简单原因,虽然事情通常更为复杂。

社会性动物很容易按照特质分类,变成我们和他们。为了内部的向心力和团结,归咎“他们”是非常有效的手段。

相比于单个领导人,我们所目睹的社会改善主要由于来自组织机构和科技进步。他们才是真正的幕后英雄。The invisible actors behind most human success are prosaic and dull compared to great, all-powerful leaders.

- 寻找原因而非罪犯:当坏事发生,别找特定的个人或群体来怪罪,而是想到这背后可能不是有谁故意为之,转为把精力放在厘清环环相扣的各个原因或整个系统。”

- 寻找体制而非英雄:当有人自称促成某件好事,你要想一想是否即使没有特定的谁做些什么,这件事仍会发生。你要给整个体制一点掌声。

10. Urgency Instinct

A decision can be seemingly urgent and remembering that it rarely is.”

销售广告常用的手段,”最后一分钟,限时大抢购,错过今天,再等一年“等等。人为构建出来的时间紧迫性使人丧失严肃思考的能力,从而做出更轻率的决定。然而大部分的事情都远远都没有想象中的那么急迫。You have probably heard something like this before, from a salesperson or an activist. Both use a lot of the same techniques: “Act now, or lose the chance forever.” They are deliberately triggering your urgency instinct. The call to action makes you think less critically, decide more quickly, and act now. Relax. It’s almost never true. It’s almost never that urgent, and it’s almost never an either/or. You can put the book down if you like and do something else. In a week or a month or a year you can pick it up again and remind yourself of its main points, and it won’t be too late. That is actually a better way to learn than trying to cram it all in at once.

显然迅速反应也是一种[[进化论]]本能,在野外生存的远古人类必须对周围危险做出迅速反应,一头野兽来攻击人的时候没有多余时间来思考对策。那些还慢悠悠思考的人都被吃了。即使是现在急迫型直觉也依然有效,因为仍有一些需要立刻做出反应的事件,比如路障紧急刹车。The urgency instinct makes us want to take immediate action in the face of a perceived imminent danger. It must have served us humans well in the distant past. If we thought there might be a lion in the grass, it wasn’t sensible to do too much analysis. Those who stopped and carefully analyzed the probabilities are not our ancestors. We are the offspring of those who decided and acted quickly with insufficient information. Today, we still need the urgency instinct—for example, when a car comes out of nowhere and we need to take evasive action. But now that we have eliminated most immediate dangers and are left with more complex and often more abstract problems, the urgency instinct can also lead us astray when it comes to our understanding the world around us. It makes us stressed, amplifies our other instincts and makes them harder to control, blocks us from thinking analytically, tempts us to make up our minds too fast, and encourages us to take drastic actions that we haven’t thought through.

但做大部分决定时要学会克制这种本能。Learn to Control the Urgency Instinct. Special Offer! Today Only! When people tell me we must act now, it makes me hesitate. In most cases, they are just trying to stop me from thinking clearly.

全球变暖问题

全球变暖是有详实数据支持的客观事件,长期人类必须想办法解决面对的问题。但激进环保主义者通常用恐惧和夸张来营造急迫感。比如再过不久许多人类栖息地都将因此不复存在。恐惧和夸张削弱的数据的可靠性,长期来看也消费了关注者,降低了可信度。狼来了的故事在哪都存在。最极端的结果就像是川普这样的,已经完全不信了。

I don’t like fear.[[The Fear Instinct 恐惧思维]] Fear of war plus the panic of urgency made me see a Russian pilot and blood on the floor. Fear of pandemic plus the panic of urgency made me close the road and cause the drownings of all those mothers, children, and fishermen. Fear plus urgency make for stupid, drastic decisions with unpredictable side effects. Climate change is too important for that. It needs systematic analysis, thought-through decisions, incremental actions, and careful evaluation.”

“And I don’t like exaggeration. Exaggeration undermines the credibility of well-founded data: in this case, data showing that climate change is real, that it is largely caused by greenhouse gases from human activities such as burning fossil fuels, and that taking swift and broad action now would be cheaper than waiting until costly and unacceptable climate change happened. Exaggeration, once discovered, makes people tune out altogether.

气候难民是一个夸张出来的概念。Most concerning is the attempt to attract people to the cause by inventing the term “climate refugees.” My best understanding is that the link between climate change and migration is very, very weak. The concept of climate refugees is mostly ^^a deliberate exaggeration^^, designed to turn fear of refugees into fear of climate change, and so build a much wider base of public support for lowering CO2 emissions.

I understand the temptation to raise support by picking the worst projections and denying the huge uncertainties in the numbers. But those who care about climate change should stop scaring people with unlikely scenarios.

Let’s instead use that energy to solve the problem by taking action: action driven not by fear and urgency but by data and coolheaded analysis.

如何克制?

1. Take a breath.

When your urgency instinct is triggered, your other instincts kick in and your analysis shuts down. Ask for more time and more information. It’s rarely now or never and it’s rarely either/or.

2. Insist on the data.

If something is urgent and important, it should be measured. Beware of data that is relevant but inaccurate, or accurate but irrelevant. Only relevant and accurate data is useful.

3. Beware of fortune-tellers.

Any prediction about the future is uncertain. Be wary of predictions that fail to acknowledge that. Insist on a full range of scenarios, never just the best or worst case. Ask how often such predictions have been right before.

4. Be wary of drastic action.

Ask what the side effects will be. Ask how the idea has been tested. Step-by-step practical improvements